По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

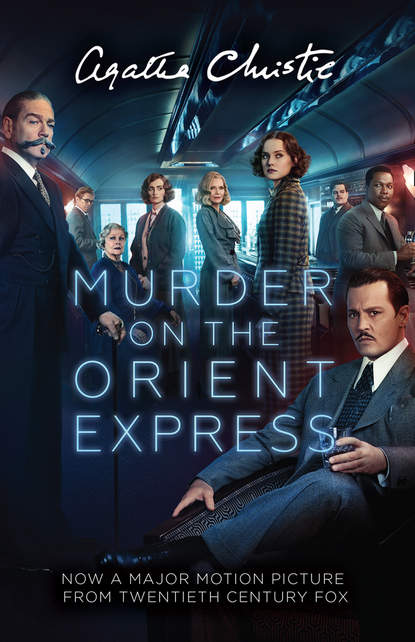

Murder on the Orient Express

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Brrrrr,’ said Lieutenant Dubosc, realizing to the full how cold he was…

II

‘Voila, Monsieur.’ The conductor displayed to Poirot with a dramatic gesture the beauty of his sleeping compartment and the neat arrangement of his luggage. ‘The little valise of Monsieur, I have placed it here.’

His outstretched hand was suggestive. Hercule Poirot placed in it a folded note.

‘Merci, Monsieur.’ The conductor became brisk and businesslike. ‘I have the tickets of Monsieur. I will also take the passport, please. Monsieur breaks his journey in Stamboul, I understand?’

M. Poirot assented.

‘There are not many people travelling, I imagine?’ he said.

‘No, Monsieur. I have only two other passengers—both English. A Colonel from India, and a young English lady from Baghdad. Monsieur requires anything?’

Monsieur demanded a small bottle of Perrier.

Five o’clock in the morning is an awkward time to board a train. There was still two hours before dawn. Conscious of an inadequate night’s sleep, and of a delicate mission successfully accomplished, M. Poirot curled up in a corner and fell asleep.

When he awoke it was half-past nine, and he sallied forth to the restaurant-car in search of hot coffee.

There was only one occupant at the moment, obviously the young English lady referred to by the conductor. She was tall, slim and dark—perhaps twenty-eight years of age. There was a kind of cool efficiency in the way she was eating her breakfast and in the way she called to the attendant to bring her more coffee, which bespoke a knowledge of the world and of travelling. She wore a dark-coloured travelling dress of some thin material eminently suitable for the heated atmosphere of the train.

M. Hercule Poirot, having nothing better to do, amused himself by studying her without appearing to do so.

She was, he judged, the kind of young woman who could take care of herself with perfect ease wherever she went. She had poise and efficiency. He rather liked the severe regularity of her features and the delicate pallor of her skin. He liked the burnished black head with its neat waves of hair, and her eyes, cool, impersonal and grey. But she was, he decided, just a little too efficient to be what he called ‘jolie femme.’

Presently another person entered the restaurant-car. This was a tall man of between forty and fifty, lean of figure, brown of skin, with hair slightly grizzled round the temples.

‘The colonel from India,’ said Poirot to himself.

The newcomer gave a little bow to the girl.

‘Morning, Miss Debenham.’

‘Good-morning, Colonel Arbuthnot.’

The Colonel was standing with a hand on the chair opposite her.

‘Any objection?’ he asked.

‘Of course not. Sit down.’

‘Well, you know, breakfast isn’t always a chatty meal.’

‘I should hope not. But I don’t bite.’

The Colonel sat down.

‘Boy,’ he called in peremptory fashion.

He gave an order for eggs and coffee.

His eyes rested for a moment on Hercule Poirot, but they passed on indifferently. Poirot, reading the English mind correctly, knew that he had said to himself, ‘Only some damned foreigner.’

True to their nationality, the two English people were not chatty. They exchanged a few brief remarks, and presently the girl rose and went back to her compartment.

At lunch time the other two again shared a table and again they both completely ignored the third passenger. Their conversation was more animated than at breakfast. Colonel Arbuthnot talked of the Punjab, and occasionally asked the girl a few questions about Baghdad where it became clear that she had been in a post as governess. In the course of conversation they discovered some mutual friends which had the immediate effect of making them more friendly and less stiff. They discussed old Tommy Somebody and Jerry Someone Else. The Colonel inquired whether she was going straight through to England or whether she was stopping in Stamboul.

‘No, I’m going straight on.’

‘Isn’t that rather a pity?’

‘I came out this way two years ago and spent three days in Stamboul then.’

‘Oh, I see. Well, I may say I’m very glad you are going right through, because I am.’

He made a kind of clumsy little bow, flushing a little as he did so.

‘He is susceptible, our Colonel,’ thought Hercule Poirot to himself with some amusement. ‘The train, it is as dangerous as a sea voyage!’

Miss Debenham said evenly that that would be very nice. Her manner was slightly repressive.

The Colonel, Hercule Poirot noticed, accompanied her back to her compartment. Later they passed through the magnificent scenery of the Taurus. As they looked down towards the Cilician Gates, standing in the corridor side by side, a sigh came suddenly from the girl. Poirot was standing near them and heard her murmur:

‘It’s so beautiful! I wish—I wish—’

‘Yes?’

‘I wish, I could enjoy it!’

Arbuthnot did not answer. The square line of his jaw seemed a little sterner and grimmer.

‘I wish to Heaven you were out of all this,’ he said.

‘Hush, please. Hush.’

‘Oh! it’s all right.’ He shot a slightly annoyed glance in Poirot’s direction. Then he went on: ‘But I don’t like the idea of your being a governess—at the beck and call of tyrannical mothers and their tiresome brats.’

She laughed with just a hint of uncontrol in the sound.

‘Oh! you mustn’t think that. The downtrodden governess is quite an exploded myth. I can assure you that it’s the parents who are afraid of being bullied by me.’

They said no more. Arbuthnot was, perhaps, ashamed of his outburst.

‘Rather an odd little comedy that I watch here,’ said Poirot to himself thoughtfully.

He was to remember that thought of his later.