По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

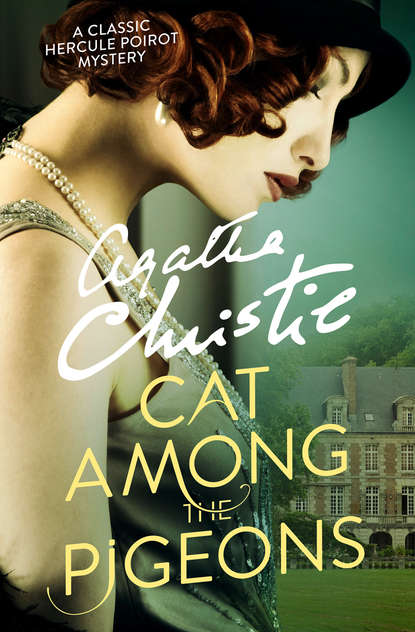

Cat Among the Pigeons

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She was saying to herself:

‘To be back again! To be here…It seems years…’ She fell over a rake, and the young gardener put out an arm and said:

‘Steady, miss.’

Eileen Rich said ‘Thank you,’ without looking at him.

VI

Miss Rowan and Miss Blake, the two junior mistresses, were strolling towards the Sports Pavilion. Miss Rowan was thin and dark and intense, Miss Blake was plump and fair. They were discussing with animation their recent adventures in Florence: the pictures they had seen, the sculpture, the fruit blossom, and the attentions (hoped to be dishonourable) of two young Italian gentlemen.

‘Of course one knows,’ said Miss Blake, ‘how Italians go on.’

‘Uninhibited,’ said Miss Rowan, who had studied Psychology as well as Economics. ‘Thoroughly healthy, one feels. No repressions.’

‘But Guiseppe was quite impressed when he found I taught at Meadowbank,’ said Miss Blake. ‘He became much more respectful at once. He has a cousin who wants to come here, but Miss Bulstrode was not sure she had a vacancy.’

‘Meadowbank is a school that really counts,’ said Miss Rowan, happily. ‘Really, the new Sports Pavilion looks most impressive. I never thought it would be ready in time.’

‘Miss Bulstrode said it had to be,’ said Miss Blake in the tone of one who has said the last word.

‘Oh,’ she added in a startled kind of way.

The door of the Sports Pavilion had opened abruptly, and a bony young woman with ginger-coloured hair emerged. She gave them a sharp unfriendly stare and moved rapidly away.

‘That must be the new Games Mistress,’ said Miss Blake. ‘How uncouth!’

‘Not a very pleasant addition to the staff,’ said Miss Rowan. ‘Miss Jones was always so friendly and sociable.’

‘She absolutely glared at us,’ said Miss Blake resentfully.

They both felt quite ruffled.

VII

Miss Bulstrode’s sitting-room had windows looking out in two directions, one over the drive and lawn beyond, and another towards a bank of rhododendrons behind the house. It was quite an impressive room, and Miss Bulstrode was rather more than quite an impressive woman. She was tall, and rather noble looking, with well-dressed grey hair, grey eyes with plenty of humour in them, and a firm mouth. The success of her school (and Meadowbank was one of the most successful schools in England) was entirely due to the personality of its Headmistress. It was a very expensive school, but that was not really the point. It could be put better by saying that though you paid through the nose, you got what you paid for.

Your daughter was educated in the way you wished, and also in the way Miss Bulstrode wished, and the result of the two together seemed to give satisfaction. Owing to the high fees, Miss Bulstrode was able to employ a full staff. There was nothing mass produced about the school, but if it was individualistic, it also had discipline. Discipline without regimentation, was Miss Bulstrode’s motto. Discipline, she held, was reassuring to the young, it gave them a feeling of security; regimentation gave rise to irritation. Her pupils were a varied lot. They included several foreigners of good family, often foreign royalty. There were also English girls of good family or of wealth, who wanted a training in culture and the arts, with a general knowledge of life and social facility who would be turned out agreeable, well groomed and able to take part in intelligent discussion on any subject. There were girls who wanted to work hard and pass entrance examinations, and eventually take degrees and who, to do so, needed only good teaching and special attention. There were girls who had reacted unfavourably to school life of the conventional type. But Miss Bulstrode had her rules, she did not accept morons, or juvenile delinquents, and she preferred to accept girls whose parents she liked, and girls in whom she herself saw a prospect of development. The ages of her pupils varied within wide limits. There were girls who would have been labelled in the past as ‘finished’, and there were girls little more than children, some of them with parents abroad, and for whom Miss Bulstrode had a scheme of interesting holidays. The last and final court of appeal was Miss Bulstrode’s own approval.

She was standing now by the chimneypiece listening to Mrs Gerald Hope’s slightly whining voice. With great foresight, she had not suggested that Mrs Hope should sit down.

‘Henrietta, you see, is very highly strung. Very highly strung indeed. Our doctor says—’

Miss Bulstrode nodded, with gentle reassurance, refraining from the caustic phrase she sometimes was tempted to utter.

‘Don’t you know, you idiot, that that is what every fool of a woman says about her child?’

She spoke with firm sympathy.

‘You need have no anxiety, Mrs Hope. Miss Rowan, a member of our staff, is a fully trained psychologist. You’ll be surprised, I’m sure, at the change you’ll find in Henrietta’ (Who’s a nice intelligent child, and far too good for you) ‘after a term or two here.’

‘Oh I know. You did wonders with the Lambeth child—absolutely wonders! So I am quite happy. And I—oh yes, I forgot. We’re going to the South of France in six weeks’ time. I thought I’d take Henrietta. It would make a little break for her.’

‘I’m afraid that’s quite impossible,’ said Miss Bulstrode, briskly and with a charming smile, as though she were granting a request instead of refusing one.

‘Oh! but—’ Mrs Hope’s weak petulant face wavered, showed temper. ‘Really, I must insist. After all, she’s my child.’

‘Exactly. But it’s my school,’ said Miss Bulstrode.

‘Surely I can take the child away from a school any time I like?’

‘Oh yes,’ said Miss Bulstrode. ‘You can. Of course you can. But then, I wouldn’t have her back.’

Mrs Hope was in a real temper now.

‘Considering the size of the fees I pay here—’

‘Exactly,’ said Miss Bulstrode. ‘You wanted my school for your daughter, didn’t you? But it’s take it as it is, or leave it. Like that very charming Balenciaga model you are wearing. It is Balenciaga, isn’t it? It is so delightful to meet a woman with real clothes sense.’

Her hand enveloped Mrs Hope’s, shook it, and imperceptibly guided her towards the door.

‘Don’t worry at all. Ah, here is Henrietta waiting for you.’ (She looked with approval at Henrietta, a nice well-balanced intelligent child if ever there was one, and who deserved a better mother.) ‘Margaret, take Henrietta Hope to Miss Johnson.’

Miss Bulstrode retired into her sitting-room and a few moments later was talking French.

‘But certainly, Excellence, your niece can study modern ballroom dancing. Most important socially. And languages, also, are most necessary.’

The next arrivals were prefaced by such a gust of expensive perfume as almost to knock Miss Bulstrode backwards.

‘Must pour a whole bottle of the stuff over herself every day,’ Miss Bulstrode noted mentally, as she greeted the exquisitely dressed dark-skinned woman.

‘Enchantée, Madame.’

Madame giggled very prettily.

The big bearded man in Oriental dress took Miss Bulstrode’s hand, bowed over it, and said in very good English, ‘I have the honour to bring to you the Princess Shaista.’

Miss Bulstrode knew all about her new pupil who had just come from a school in Switzerland, but was a little hazy as to who it was escorting her. Not the Emir himself, she decided, probably the Minister, or Chargé d’Affaires. As usual when in doubt, she used that useful title Excellence, and assured him that Princess Shaista would have the best of care.

Shaista was smiling politely. She was also fashionably dressed and perfumed. Her age, Miss Bulstrode knew, was fifteen, but like many Eastern and Mediterranean girls, she looked older—quite mature. Miss Bulstrode spoke to her about her projected studies and was relieved to find that she answered promptly in excellent English and without giggling. In fact, her manners compared favourably with the awkward ones of many English school girls of fifteen. Miss Bulstrode had often thought that it might be an excellent plan to send English girls abroad to the Near Eastern countries to learn courtesy and manners there. More compliments were uttered on both sides and then the room was empty again though still filled with such heavy perfume that Miss Bulstrode opened both windows to their full extent to let some of it out.

The next comers were Mrs Upjohn and her daughter Julia.

Mrs Upjohn was an agreeable young woman in the late thirties with sandy hair, freckles and an unbecoming hat which was clearly a concession to the seriousness of the occasion, since she was obviously the type of young woman who usually went hatless.

Julia was a plain freckled child, with an intelligent forehead, and an air of good humour.

The preliminaries were quickly gone through and Julia was despatched via Margaret to Miss Johnson, saying cheerfully as she went, ‘So long, Mum. Do be careful lighting that gas heater now that I’m not there to do it.’