По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

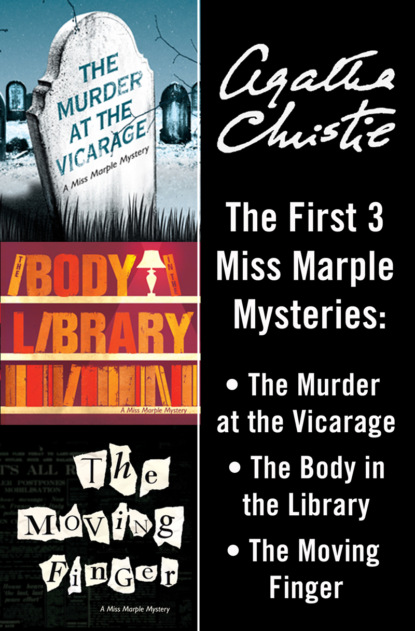

Miss Marple 3-Book Collection 1: The Murder at the Vicarage, The Body in the Library, The Moving Finger

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

And on that she took her departure, shaking her head with a kind of ominous melancholy. Melchett muttered under his breath: ‘No such luck.’ Then his face grew grave, and he looked inquiringly at Inspector Slack.

That worthy nodded his head slowly.

‘This about settles it, sir. That’s three people who heard the shot. We’ve got to find out now who fired it. This business of Mr Redding’s has delayed us. But we’ve got several starting points. Thinking Mr Redding was guilty, I didn’t bother to look into them. But that’s all changed now. And now one of the first things to do is look up that telephone call.’

‘Mrs Price Ridley’s?’

The Inspector grinned.

‘No – though I suppose we’d better make a note of that or else we shall have the old girl bothering in here again. No, I meant that fake call that got the Vicar out of the way.’

‘Yes,’ said Melchett, ‘that’s important.’

‘And the next thing is to find out what everyone was doing that evening between six and seven. Everyone at Old Hall, I mean, and pretty well everyone in the village as well.’

I gave a sigh.

‘What wonderful energy you have, Inspector Slack.’

‘I believe in hard work. We’ll begin by just noting down your own movements, Mr Clement.’

‘Willingly. The telephone call came through about half-past five.’

‘A man’s voice, or a woman’s?’

‘A woman’s. At least it sounded like a woman’s. But of course I took it for granted it was Mrs Abbott speaking.’

‘You didn’t recognize it as being Mrs Abbott’s?’

‘No, I can’t say I did. I didn’t notice the voice particularly or think about it.’

‘And you started right away? Walked? Haven’t you got a bicycle?’

‘No.’

‘I see. So it took you – how long?’

‘It’s very nearly two miles, whichever way you go.’

‘Through Old Hall woods is the shortest way, isn’t it?’

‘Actually, yes. But it’s not particularly good going. I went and came back by the footpath across the fields.’

‘The one that comes out opposite the Vicarage gate?’

‘Yes.’

‘And Mrs Clement?’

‘My wife was in London. She arrived back by the 6.50 train.’

‘Right. The maid I’ve seen. That finishes with the Vicarage. I’ll be off to Old Hall next. And then I want an interview with Mrs Lestrange. Queer, her going to see Protheroe the night before he was killed. A lot of queer things about this case.’

I agreed.

Glancing at the clock, I realized that it was nearly lunch time. I invited Melchett to partake of pot luck with us, but he excused himself on the plea of having to go to the Blue Boar. The Blue Boar gives you a first-rate meal of the joint and two-vegetable type. I thought his choice was a wise one. After her interview with the police, Mary would probably be feeling more temperamental than usual.

Chapter 14 (#ulink_0d09c2f2-c2f1-5f83-bfb5-81dbbc2cd755)

On my way home, I ran into Miss Hartnell and she detained me at least ten minutes, declaiming in her deep bass voice against the improvidence and ungratefulness of the lower classes. The crux of the matter seemed to be that The Poor did not want Miss Hartnell in their houses. My sympathies were entirely on their side. I am debarred by my social standing from expressing my prejudices in the forceful manner they do.

I soothed her as best I could and made my escape.

Haydock overtook me in his car at the corner of the Vicarage road. ‘I’ve just taken Mrs Protheroe home,’ he called.

He waited for me at the gate of his house.

‘Come in a minute,’ he said. I complied.

‘This is an extraordinary business,’ he said, as he threw his hat on a chair and opened the door into his surgery.

He sank down on a shabby leather chair and stared across the room. He looked harried and perplexed.

I told him that we had succeeded in fixing the time of the shot. He listened with an almost abstracted air.

‘That lets Anne Protheroe out,’ he said. ‘Well, well, I’m glad it’s neither of those two. I like ’em both.’

I believed him, and yet it occurred to me to wonder why, since, as he said, he liked them both, their freedom from complicity seemed to have had the result of plunging him in gloom. This morning he had looked like a man with a weight lifted from his mind, now he looked thoroughly rattled and upset.

And yet I was convinced that he meant what he said. He was fond of both Anne Protheroe and Lawrence Redding. Why, then, this gloomy absorption? He roused himself with an effort.

‘I meant to tell you about Hawes. All this business has driven him out of my mind.’

‘Is he really ill?’

‘There’s nothing radically wrong with him. You know, of course, that he’s had Encephalitis Lethargica, sleepy sickness, as it’s commonly called?’

‘No,’ I said, very much surprised, ‘I didn’t know anything of the kind. He never told me anything about it. When did he have it?’

‘About a year ago. He recovered all right – as far as one ever recovers. It’s a strange disease – has a queer moral effect. The whole character may change after it.’

He was silent for a moment or two, and then said:

‘We think with horror now of the days when we burnt witches. I believe the day will come when we will shudder to think that we ever hanged criminals.’

‘You don’t believe in capital punishment?’

‘It’s not so much that.’ He paused. ‘You know,’ he said slowly, ‘I’d rather have my job than yours.’