По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

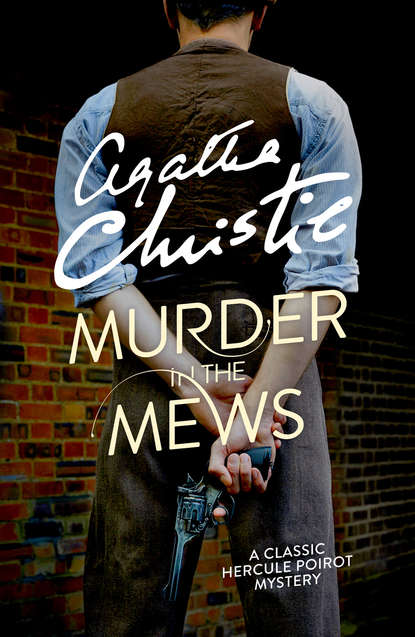

Murder in the Mews

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Well, of course, I can’t remember the exact words.’

‘My information is that what you actually said was, “Well, think it over and let me know.”’

‘Let me see, yes I believe you’re right. Not exactly that. I think I was suggesting she should let me know when she was free.’

‘Not quite the same thing, is it?’ said Japp.

Major Eustace shrugged his shoulders.

‘My dear fellow, you can’t expect a man to remember word for word what he said on any given occasion.’

‘And what did Mrs Allen reply?’

‘She said she’d give me a ring. That is, as near as I can remember.’

‘And then you said, “All right. So long.”’

‘Probably. Something of the kind anyway.’

Japp said quietly:

‘You say that Mrs Allen asked you to advise her about her investments. Did she, by any chance, entrust you with the sum of two hundred pounds in cash to invest for her?’

Eustace’s face flushed a dark purple. He leaned forward and growled out:

‘What the devil do you mean by that?’

‘Did she or did she not?’

‘That’s my business, Mr Chief Inspector.’

Japp said quietly:

‘Mrs Allen drew out the sum of two hundred pounds in cash from her bank. Some of the money was in five-pound notes. The numbers of these can, of course, be traced.’

‘What if she did?’

‘Was the money for investment—or was it—blackmail, Major Eustace?’

‘That’s a preposterous idea. What next will you suggest?’

Japp said in his most official manner:

‘I think, Major Eustace, that at this point I must ask you if you are willing to come to Scotland Yard and make a statement. There is, of course, no compulsion and you can, if you prefer it, have your solicitor present.’

‘Solicitor? What the devil should I want with a solicitor? And what are you cautioning me for?’

‘I am inquiring into the circumstances of the death of Mrs Allen.’

‘Good God, man, you don’t suppose—Why, that’s nonsense! Look here, what happened was this. I called round to see Barbara by appointment—’

‘That was at what time?’

‘At about half-past nine, I should say. We sat and talked—’

‘And smoked?’

‘Yes, and smoked. Anything damaging in that?’ demanded the major belligerently.

‘Where did this conversation take place?’

‘In the sitting-room. Left of the door as you go in. We talked together quite amicably, as I say. I left a little before half-past ten. I stayed for a minute on the doorstep for a few last words—’

‘Last words—precisely,’ murmured Poirot.

‘Who are you, I’d like to know?’ Eustace turned and spat the words at him. ‘Some kind of damned dago! What are you butting in for?’

‘I am Hercule Poirot,’ said the little man with dignity.

‘I don’t care if you are the Achilles statue. As I say, Barbara and I parted quite amicably. I drove straight to the Far East Club. Got there at five and twenty to eleven and went straight up to the card-room. Stayed there playing bridge until one-thirty. Now then, put that in your pipe and smoke it.’

‘I do not smoke the pipe,’ said Poirot. ‘It is a pretty alibi you have there.’

‘It should be a pretty cast iron one anyway! Now then, sir,’ he looked at Japp. ‘Are you satisfied?’

‘You remained in the sitting-room throughout your visit?’

‘Yes.’

‘You did not go upstairs to Mrs Allen’s own boudoir?’

‘No, I tell you. We stayed in the one room and didn’t leave it.’

Japp looked at him thoughtfully for a minute or two. Then he said:

‘How many sets of cuff links have you?’

‘Cuff links? Cuff links? What’s that got to do with it?’

‘You are not bound to answer the question, of course.’

‘Answer it? I don’t mind answering it. I’ve got nothing to hide. And I shall demand an apology. There are these …’ he stretched out his arms.

Japp noted the gold and platinum with a nod.

‘And I’ve got these.’

He rose, opened a drawer and taking out a case, he opened it and shoved it rudely almost under Japp’s nose.