По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

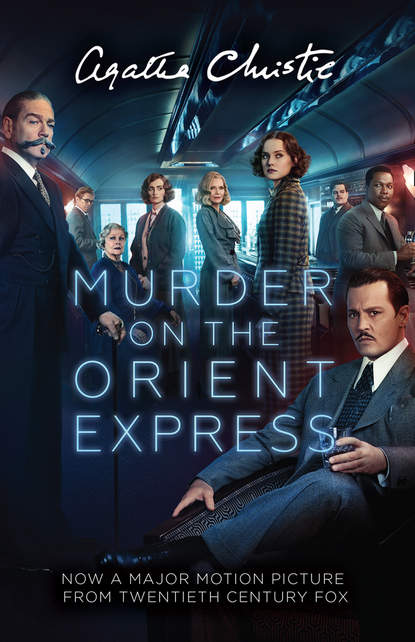

Murder on the Orient Express

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Certainly,’ said M. Bouc.

He turned to the chef de train.

‘Get M. MacQueen to come here.’

The chef de train left the carriage.

The conductor returned with a bundle of passports and tickets. M. Bouc took them from him.

‘Thank you, Michel. It would be best now, I think, if you were to go back to your post. We will take your evidence formally later.’

‘Very good, Monsieur.’

Michel in his turn left the carriage.

‘After we have seen young MacQueen,’ said Poirot, ‘perhaps M. le docteur will come with me to the dead man’s carriage.’

‘Certainly.’

‘After we have finished there—’

But at this moment the chef de train returned with Hector MacQueen.

M. Bouc rose.

‘We are a little cramped here,’ he said pleasantly. ‘Take my seat, M. MacQueen. M. Poirot will sit opposite you—so.’

He turned to the chef de train.

‘Clear all the people out of the restaurant-car,’ he said, ‘and let it be left free for M. Poirot. You will conduct your interviews there, mon cher?’

‘It would be the most convenient, yes,’ agreed Poirot.

MacQueen had stood looking from one to the other, not quite following the rapid flow of French.

‘Qu’est ce qu’il y a?’ he began laboriously. ‘Pourquoi—?’

With a vigorous gesture Poirot motioned him to the seat in the corner. He took it and began once more.

‘Pourquoi—?’ then, checking himself and relapsing into his own tongue, ‘What’s up on the train? Has anything happened?’

He looked from one man to another.

Poirot nodded.

‘Exactly. Something has happened. Prepare yourself for a shock. Your employer, M. Ratchett, is dead!’

MacQueen’s mouth pursed itself in a whistle. Except that his eyes grew a shade brighter, he showed no signs of shock or distress.

‘So they got him after all,’ he said.

‘What exactly do you mean by that phrase, M. MacQueen?’ MacQueen hesitated.

‘You are assuming,’ said Poirot, ‘that M. Ratchett was murdered?’

‘Wasn’t he?’ This time MacQueen did show surprise. ‘Why, yes,’ he said slowly. ‘That’s just what I did think. Do you mean he just died in his sleep? Why, the old man was as tough as—as tough—’

He stopped, at a loss for a simile.

‘No, no,’ said Poirot. ‘Your assumption was quite right. Mr Ratchett was murdered. Stabbed. But I should like to know why you were so sure it was murder, and not just—death.’

MacQueen hesitated.

‘I must get this clear,’ he said. ‘Who exactly are you? And where do you come in?’

‘I represent the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons Lits.’ He paused, then added, ‘I am a detective. My name is Hercule Poirot.’

If he expected an effect he did not get one. MacQueen said merely, ‘Oh, yes?’ and waited for him to go on.

‘You know the name, perhaps.’

‘Why, it does seem kind of familiar—only I always thought it was a woman’s dressmaker.’

Hercule Poirot looked at him with distaste.

‘It is incredible!’ he said.

‘What’s incredible?’

‘Nothing. Let us advance with the matter in hand. I want you to tell me, M. MacQueen, all that you know about the dead man. You were not related to him?’

‘No. I am—was—his secretary.’

‘For how long have you held that post?’

‘Just over a year.’

‘Please give me all the information you can.’

‘Well, I met Mr Ratchett just over a year ago when I was in Persia—’

Poirot interrupted.

‘What were you doing there?’

‘I had come over from New York to look into an oil concession. I don’t suppose you want to hear all about that. My friends and I had been let in rather badly over it. Mr Ratchett was in the same hotel. He had just had a row with his secretary. He offered me the job and I took it. I was at a loose end, and glad to find a well-paid job ready made, as it were.’

‘And since then?’