По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

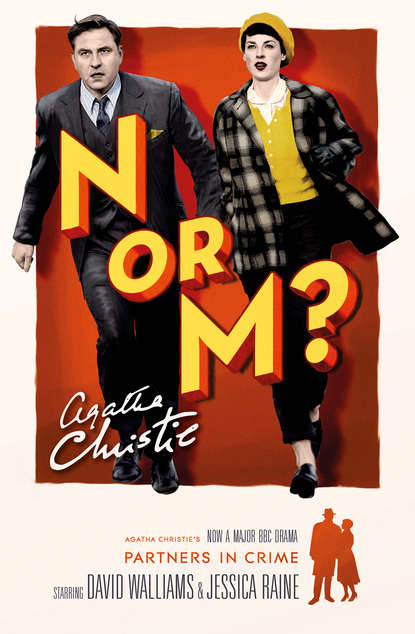

N or M?

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Nonsense,’ said Mr Cayley. ‘This war is going to last at least six years.’

‘Oh, Mr Cayley,’ protested Tuppence. ‘You don’t really think so?’

Mr Cayley was peering about him suspiciously.

‘Now I wonder,’ he murmured. ‘Is there a draught? Perhaps it would be better if I moved my chair back into the corner.’

The resettlement of Mr Cayley took place. His wife, an anxious-faced woman who seemed to have no other aim in life than to minister to Mr Cayley’s wants, manipulating cushions and rugs, asking from time to time: ‘Now how is that, Alfred? Do you think that will be all right? Ought you, perhaps, to have your sun-glasses? There is rather a glare this morning.’

Mr Cayley said irritably:

‘No, no. Don’t fuss, Elizabeth. Have you got my muffler? No, no, my silk muffler. Oh well, it doesn’t matter. I dare say this will do—for once. But I don’t want to get my throat overheated, and wool—in this sunlight—well, perhaps you had better fetch the other.’ He turned his attention back to matters of public interest. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘I give it six years.’

He listened with pleasure to the protests of the two women.

‘You dear ladies are just indulging in what we call wishful thinking. Now I know Germany. I may say I know Germany extremely well. In the course of my business before I retired I used to be constantly to and fro. Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, I know them all. I can assure you that Germany can hold out practically indefinitely. With Russia behind her—’

Mr Cayley plunged triumphantly on, his voice rising and falling in pleasurably melancholy cadences, only interrupted when he paused to receive the silk muffler his wife brought him and wind it round his throat.

Mrs Sprot brought out Betty and plumped her down with a small woollen dog that lacked an ear and a woolly doll’s jacket.

‘There, Betty,’ she said. ‘You dress up Bonzo ready for his walk while Mummy gets ready to go out.’

Mr Cayley’s voice droned on, reciting statistics and figures, all of a depressing character. The monologue was punctuated by a cheerful twittering from Betty talking busily to Bonzo in her own language.

‘Truckle—truckly—pah bat,’ said Betty. Then, as a bird alighted near her, she stretched out loving hands to it and gurgled. The bird flew away and Betty glanced round the assembled company and remarked clearly:

‘Dicky,’ and nodded her head with great satisfaction.

‘That child is learning to talk in the most wonderful way,’ said Miss Minton. ‘Say “Ta ta”, Betty. “Ta ta.”’

Betty looked at her coldly and remarked:

‘Gluck!’

Then she forced Bonzo’s one arm into his woolly coat and, toddling over to a chair, picked up the cushion and pushed Bonzo behind it. Chuckling gleefully, she said with terrific pains:

‘Hide! Bow wow. Hide!’

Miss Minton, acting as a kind of interpreter, said with vicarious pride:

‘She loves hide-and-seek. She’s always hiding things.’ She cried out with exaggerated surprise:

‘Where is Bonzo? Where is Bonzo? Where can Bonzo have gone?’

Betty flung herself down and went into ecstasies of mirth.

MrCayley, finding attention diverted from his explanation of Germany’s methods of substitution of raw materials, looked put out and coughed aggressively.

Mrs Sprot came out with her hat on and picked up Betty.

Attention returned to Mr Cayley.

‘You were saying, Mr Cayley?’ said Tuppence.

But Mr Cayley was affronted. He said coldly:

‘That woman is always plumping that child down and expecting people to look after it. I think I’ll have the woollen muffler after all, dear. The sun is going in.’

‘Oh, but, Mr Cayley, do go on with what you were telling us. It was so interesting,’ said Miss Minton.

Mollified, Mr Cayley weightily resumed his discourse, drawing the folds of the woolly muffler closer round his stringy neck.

‘As I was saying, Germany has so perfected her system of—’

Tuppence turned to Mrs Cayley, and asked:

‘What do you think about the war, Mrs Cayley?’

Mrs Cayley jumped.

‘Oh, what do I think? What—what do you mean?’

‘Do you think it will last as long as six years?’

Mrs Cayley said doubtfully:

‘Oh, I hope not. It’s a very long time, isn’t it?’

‘Yes. A long time. What do you really think?’

Mrs Cayley seemed quite alarmed by the question. She said:

‘Oh, I—I don’t know. I don’t know at all. Alfred says it will.’

‘But you don’t think so?’

‘Oh, I don’t know. It’s difficult to say, isn’t it?’

Tuppence felt a wave of exasperation. The chirruping Miss Minton, the dictatorial Mr Cayley, the nit-witted Mrs Cayley—were these people really typical of her fellow-countrymen? Was Mrs Sprot any better with her slightly vacant face and boiled gooseberry eyes? What could she, Tuppence, ever find out here? Not one of these people, surely—

Her thought was checked. She was aware of a shadow. Someone behind her who stood between her and the sun. She turned her head.

Mrs Perenna, standing on the terrace, her eyes on the group. And something in those eyes—scorn, was it? A kind of withering contempt. Tuppence thought:

‘I must find out more about Mrs Perenna.’

Tommy was establishing the happiest of relationships with Major Bletchley.