По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

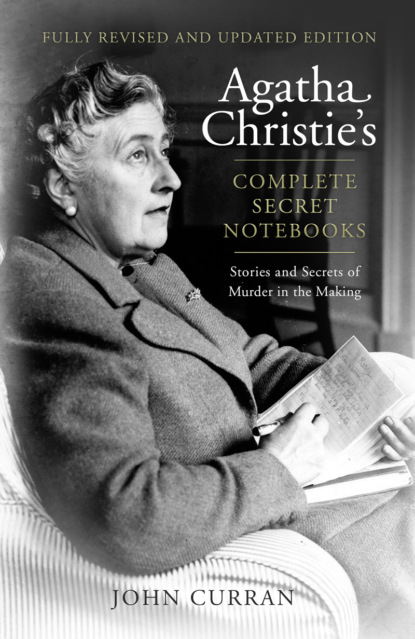

Agatha Christie’s Complete Secret Notebooks

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

J. The weight over the door (if J) or definitely dies – little black book missing [Chapter 18]

K. Charles and Sophia Murder – what does murder do to anyone? [Chapter 4]

The notes for Crooked House also illustrate a seemingly contradictory and misleading aspect of the Notebooks. It is quite common to come across pages with diagonal lines drawn across them. At first glance it would seem, understandably, that these were rejected ideas but a closer look shows that the exact opposite was the case. A line across a page indicates Work Done or Idea Used. This was a habit through her most prolific period although she tended to leave the pages, used or not, unmarked in her later writing life.

Ten Little Possibilities

In ‘The Affair at the Bungalow’, written in 1928 and collected in The Thirteen Problems (1932), Mrs Bantry comes up with reasons for someone to steal their own jewels:

‘And anyway I can think of hundreds of reasons. She might have wanted money at once … so she pretends the jewels are stolen and sells them secretly. Or she may have been blackmailed by someone who threatened to tell her husband … Or she may have already sold the jewels … so she had to do something about it. That’s done a good deal in books. Or perhaps he was going to have them reset and she’d got paste replicas. Or – here’s a very good idea – and not so much done in books – she pretends they are stolen, gets in an awful state and he gives her a fresh lot.’

In Third Girl (1966) Norma Restarick comes to Poirot and tells him that she might have committed a murder. In Chapter 2, Mrs Ariadne Oliver, that well-known detective novelist, imagines some situations that could account for this possibility:

Mrs Oliver began to brighten as she set her ever prolific imagination to work. ‘She could have run over someone in her car and not stopped. She could have been assaulted by a man on a cliff and struggled with him and managed to push him over. She could have given someone else the wrong medicine by mistake. She could have gone to one of those purple pill parties and had a fight with someone. She could have come to and found she’d stabbed someone. She … might have been a nurse in the operating theatre and administered the wrong anaesthetic …’

In Chapter 8 of Dead Man’s Folly (1956) Mrs Oliver again lets her imagination roam when considering possible motives for the murder of schoolgirl Marlene Tucker:

‘She could have been murdered by someone who just likes murdering girls … Or she might have known some secrets about somebody’s love affairs, or she may have seen someone bury a body at night or she may have seen somebody who was concealing his identity – or she may have known some secret about where some treasure was buried during the war. Or the man in the launch may have thrown somebody into the river and she saw it from the window of the boathouse – or she may have even got hold of some very important message in secret code and not known what it was herself …’ It was clear that she could have gone on in this vein for some time although it seemed to the Inspector that she had already envisaged every possibility, likely or unlikely.

These extracts from stories, written almost 40 years apart, illustrate, via her characters, Christie’s greatest strength: her ability to weave seemingly endless variations around one idea. There can be little doubt that these are Agatha Christie herself speaking and we can see from the Notebooks that this is exactly what she did. Throughout her career her ideas were consistently drawn from the world with which her readers were familiar – teeth, dogs, stamps (as below), mirrors, telephones, medicines – and upon these foundations she built her ingenious constructions. She explored universal themes in some of her later books (guilt and innocence in Ordeal by Innocence, evil in The Pale Horse, international unrest in Cat among the Pigeons and Passenger to Frankfurt), but still firmly rooted in the everyday.

The opening of The ABC Murders (note the reference to a single ‘Murder’), illustrating the use of crossing-out as an indication of work completed.

Although it is not possible to be absolutely sure, there is no reason to suppose that listings of ideas and their variations were written at different times; I have no doubt that she rattled off variations and possibilities as fast as she could write, which probably accounts for the handwriting. In many cases it is possible to show that the list is written with the same pen and in the same style of handwriting. The outline of One, Two, Buckle my Shoe provides a good example as she considers:

Man marries secretly one of the twins

Or

Man was really already married [this was the option adopted]

Or

Barrister’s ‘sister’ who lives with him (really wife)

Or

Double murder – that is to say – A poisons B – B stabs A – but really owing to plan by C

Or

Blackmailing wife finds out – then she is found dead

Or

He really likes wife – goes off to start life again with her

Or

Dentists killed – 1 London – 1 County

A few pages later in the same Notebook, also in connection with One, Two, Buckle my Shoe, she tries further variations on the same theme, this time introducing ‘Sub Ideas’.

Pos. A. 1st wife still alive –

A. (a) knows all – co-operating with him

(b) does not know – that he is secret service

Pos. B 1st wife dead – someone recognises him – ‘I was a great friend of your wife, you know –’

In either case – crime is undertaken to suppress fact of 1st marriage and elaborate preparations undertaken

C. Single handed

D. Co-operation of wife as secretary

Sub Idea C

The ‘friends’ Miss B and Miss R – one goes to dentist

Or

Does wife go to a certain dentist?

Miss B makes app[ointment] – with dentist – Miss R keeps it

Miss R’s teeth labelled under Miss B’s name

Also from Notebook 35, but this time in connection with Five Little Pigs, we find very basic questions and possibilities under consideration:

Did mother murder –

A. Husband

B. Lover

C. Rich uncle or guardian

D. Another woman (jealousy)

Who were the other people

During the planning of Mrs McGinty’s Dead, the four murders in the past, around which the plot is built, provided an almost infinite number of possibilities and she worked her way methodically through them, considering every character living in Broadhinny, the scene of the novel, as a possible participant in the earlier murders. In this extract from Notebook 43 she tries various scenarios, underlining the possible killer in each case.

Which?

1. A. False – elderly Cranes – with daughter (girl – Evelyn)