По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

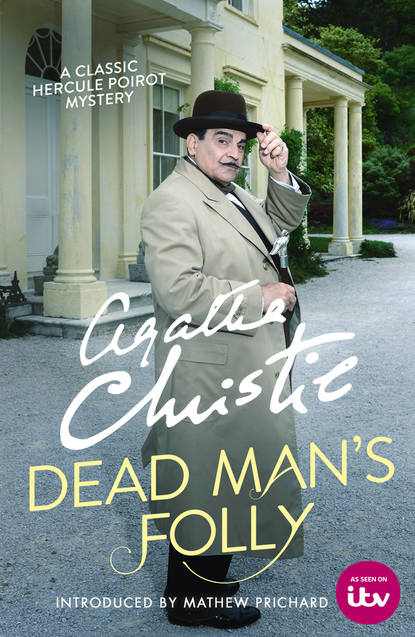

Dead Man’s Folly

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Oh, but of course,’ she said, ‘there’s a story. Like in a magazine serial – a synopsis.’ She turned to Captain Warburton. ‘Have you got the leaflets?’

‘They’ve not come from the printers yet.’

‘But they promised!’

‘I know. I know. Everyone always promises. They’ll be ready this evening at six. I’m going in to fetch them in the car.’

‘Oh, good.’

Mrs Oliver gave a deep sigh and turned to Poirot.

‘Well, I’ll have to tell it you, then. Only I’m not very good at telling things. I mean if I write things, I get them perfectly clear, but if I talk, it always sounds the most frightful muddle; and that’s why I never discuss my plots with anyone. I’ve learnt not to, because if I do, they just look at me blankly and say “– er – yes, but – I don’t see what happened – and surely that can’t possibly make a book.” So damping. And not true, because when I write it, it does!’

Mrs Oliver paused for breath, and then went on:

‘Well, it’s like this. There’s Peter Gaye who’s a young Atom Scientist and he’s suspected of being in the pay of the Communists, and he’s married to this girl, Joan Blunt, and his first wife’s dead, but she isn’t, and she turns up because she’s a secret agent, or perhaps not, I mean she may really be a hiker – and the wife’s having an affair, and this man Loyola turns up either to meet Maya, or to spy upon her, and there’s a blackmailing letter which might be from the housekeeper, or again it might be the butler, and the revolver’s missing, and as you don’t know who the blackmailing letter’s to, and the hypodermic syringe fell out at dinner, and after that it disappeared…’

Mrs Oliver came to a full stop, estimating correctly Poirot’s reaction.

‘I know,’ she said sympathetically. ‘It sounds just a muddle, but it isn’t really – not in my head – and when you see the synopsis leaflet, you’ll find it’s quite clear.

‘And, anyway,’ she ended, ‘the story doesn’t really matter, does it? I mean, not to you. All you’ve got to do is to present the prizes – very nice prizes, the first’s a silver cigarette case shaped like a revolver – and say how remarkably clever the solver has been.’

Poirot thought to himself that the solver would indeed have been clever. In fact, he doubted very much that there would be a solver. The whole plot and action of the Murder Hunt seemed to him to be wrapped in impenetrable fog.

‘Well,’ said Captain Warburton cheerfully, glancing at his wrist-watch, ‘I’d better be off to the printers and collect.’

Mrs Oliver groaned.

‘If they’re not done –’

‘Oh, they’re done all right. I telephoned. So long.’

He left the room.

Mrs Oliver immediately clutched Poirot by the arm and demanded in a hoarse whisper:

‘Well?’

‘Well – what?’

‘Have you found out anything? Or spotted anybody?’

Poirot replied with mild reproof in his tones:

‘Everybody and everything seems to me completely normal.’

‘Normal?’

‘Well, perhaps that is not quite the right word. Lady Stubbs, as you say, is definitely subnormal, and Mr Legge would appear to be rather abnormal.’

‘Oh, he’s all right,’ said Mrs Oliver impatiently. ‘He’s had a nervous breakdown.’

Poirot did not question the somewhat doubtful wording of this sentence but accepted it at its face value.

‘Everybody appears to be in the expected state of nervous agitation, high excitement, general fatigue, and strong irritation, which are characteristic of preparations for this form of entertainment. If you could only indicate –’

‘Sh!’ Mrs Oliver grasped his arm again. ‘Someone’s coming.’

It was just like a bad melodrama, Poirot felt, his own irritation mounting.

The pleasant mild face of Miss Brewis appeared round the door.

‘Oh, there you are, M. Poirot. I’ve been looking for you to show you your room.’

She led him up the staircase and along a passage to a big airy room looking out over the river.

‘There is a bathroom just opposite. Sir George talks of adding more bathrooms, but to do so would sadly impair the proportions of the rooms. I hope you’ll find everything quite comfortable.’

‘Yes, indeed.’ Poirot swept an appreciative eye over the small bookstand, the reading-lamp and the box labelled ‘Biscuits’ by the bedside. ‘You seem, in this house, to have everything organized to perfection. Am I to congratulate you, or my charming hostess?’

‘Lady Stubbs’ time is fully taken up in being charming,’ said Miss Brewis, a slightly acid note in her voice.

‘A very decorative young woman,’ mused Poirot.

‘As you say.’

‘But in other respects is she not, perhaps…’ He broke off. ‘Pardon. I am indiscreet. I comment on something I ought not, perhaps, to mention.’

Miss Brewis gave him a steady look. She said dryly:

‘Lady Stubbs knows perfectly well exactly what she is doing. Besides being, as you said, a very decorative young woman, she is also a very shrewd one.’

She had turned away and left the room before Poirot’s eyebrows had fully risen in surprise. So that was what the efficient Miss Brewis thought, was it? Or had she merely said so for some reason of her own? And why had she made such a statement to him – to a newcomer? Because he was a newcomer, perhaps? And also because he was a foreigner. As Hercule Poirot had discovered by experience, there were many English people who considered that what one said to foreigners didn’t count!

He frowned perplexedly, staring absentmindedly at the door out of which Miss Brewis had gone. Then he strolled over to the window and stood looking out. As he did so, he saw Lady Stubbs come out of the house with Mrs Folliat and they stood for a moment or two talking by the big magnolia tree. Then Mrs Folliat nodded a goodbye, picked up her gardening basket and gloves and trotted off down the drive. Lady Stubbs stood watching her for a moment, then absentmindedly pulled off a magnolia flower, smelt it and began slowly to walk down the path that led through the trees to the river. She looked just once over her shoulder before she disappeared from sight. From behind the magnolia tree Michael Weyman came quietly into view, paused a moment irresolutely and then followed the tall slim figure down into the trees.

A good-looking and dynamic young man, Poirot thought. With a more attractive personality, no doubt, than that of Sir George Stubbs…

But if so, what of it? Such patterns formed themselves eternally through life. Rich middle-aged unattractive husband, young and beautiful wife with or without sufficient mental development, attractive and susceptible young man. What was there in that to make Mrs Oliver utter a peremptory summons through the telephone? Mrs Oliver, no doubt, had a vivid imagination, but…

‘But after all,’ murmured Hercule Poirot to himself, ‘I am not a consultant in adultery – or in incipient adultery.’

Could there really be anything in this extraordinary notion of Mrs Oliver’s that something was wrong? Mrs Oliver was a singularly muddle-headed woman, and how she managed somehow or other to turn out coherent detective stories was beyond him, and yet, for all her muddle-headedness she often surprised him by her sudden perception of truth.

‘The time is short – short,’ he murmured to himself. ‘Is there something wrong here, as Mrs Oliver believes? I am inclined to think there is. But what? Who is there who could enlighten me? I need to know more, much more, about the people in this house. Who is there who could inform me?’

After a moment’s reflection he seized his hat (Poirot never risked going out in the evening air with uncovered head), and hurried out of his room and down the stairs. He heard afar the dictatorial baying of Mrs Masterton’s deep voice. Nearer at hand, Sir George’s voice rose with an amorous intonation.