По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

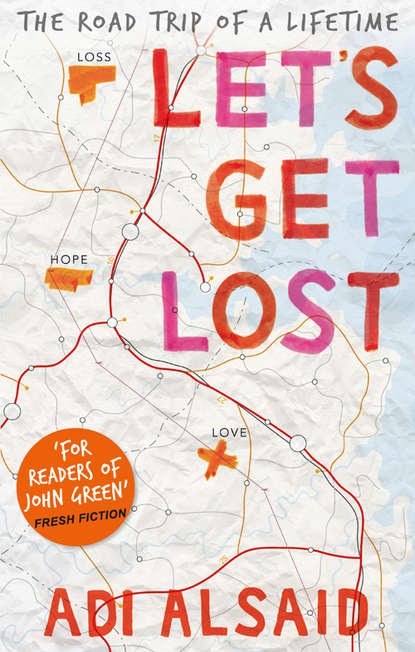

Let's Get Lost

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He could see her out of the corner of his eye, sitting quietly, moving just enough to look around the garage. Her gaze occasionally landed on Hudson, and his heart flitted in response. “Did you know that certain mechanic schools have operating rooms with viewing areas, like you’d have in med school? Just like surgeons in training, there’s only so much you can learn in a classroom. The only difference is that you don’t have to get sterilized.” Hudson peeked around the hood to catch her expression.

The girl turned to him, an eyebrow arched, containing a smile by biting her bottom lip.

“I hear some students even faint the first time they see a car getting worked on. They just can’t handle the gore,” he quipped.

“Well, sure. All that oil—who can blame them?” She smiled and shook her head at him. “Dork.”

He smiled back, then pulled her car up onto the lift so he could change the oil and the transmission fluid. What had driven him to make such a silly comment, he couldn’t say, nor could he explain why it had felt good when she called him a dork.

“Have you ever been to Mississippi before?” he asked, once the car was up.

“Can’t say that I have.”

“How long are you planning on staying?”

“I’m not sure, actually. I don’t really have an itinerary I’m sticking to. I might just be passing through.”

Hudson set up the funnel under the oil pan’s drain plug, listening for the familiar glug of the heavy liquid pouring down to the disposal bins beside the lift. He searched for something else to say, feeling an urge to confide. “Well, if you want my opinion, you shouldn’t leave until you’ve really seen the state. There’s a lot of treasures around.”

“Treasures? Of the buried variety?”

“Sure,” Hudson said. “Just, metaphorically buried.” He glanced at her, ready to catch her rolling her eyes or in some other way dismissing the comment. He’d never actually spoken the thought aloud to anyone, mostly because he expected people to think he was crazy to find Vicksburg special. This girl looked curious, though, waiting for him to go on.

“Not necessarily buried, just hidden behind everyday life. Behind all the fast-food chains and boredom. People who like Vicksburg usually just like what Vicksburg isn’t instead of all the things it is.” Hudson plugged the oil drain and started flushing out the old transmission fluid, hoping he wasn’t babbling.

“Meaning?”

“It’s not a big city, it’s not polluted, it’s not dangerous, it’s not unfamiliar.” God, he could feel himself starting to talk faster. “All of which are true, and good, sure. But it’s not what Vicksburg really is, you know? That’s the same thing as saying, ‘I like you because you’re not a murderer.’ That’s a very good quality for a person to have, but it doesn’t really tell you much about them.”

Well done, Hudson thought to himself. Keep on talking about murderers; that’s the perfect way to make a good impression. While the transmission fluid cleared out, he examined the tread on the tires, which seemed to be in decent shape, and tried to steer his little speech away from felonies.

“I’m sorry, I usually don’t go on like this. I guess you’re just easy to talk to,” Hudson said.

By some miracle, the girl was smiling at him. “Don’t be sorry. That was a solid rant.”

He grabbed a rag from his pocket and wiped his hands on it. “Thanks. Most people aren’t so interested in this stuff.”

“Well, lucky for you, I can appreciate a good rant.”

She gave him a smile and then turned to look out the garage, her eyes narrowed by the glare of the sun. Hudson wondered if he’d ever been so captivated by watching someone stare out into the distance. Even with the pretty girls he’d halfheartedly pursued, Kate and Suzanne and Ella, Hudson couldn’t remember being so unable to look away.

“So, what are some of these hidden treasures?” she asked.

He walked around the car as if he was checking on something. “Um,” he said, impressed that she was taking the conversation in stride. “I’m drawing a blank. But you know what I mean, don’t you? How sometimes you feel like you’re the only person in the world who is seeing something?”

The girl laughed, rich and warm. “I’ll tell you one: It’s quiet here,” she said. She wiped at the thin film of sweat that had gathered on her forehead, using the moisture to comb back a couple of loose strands of hair. He could hear his dad around the back, testing the engine on the semi that had come in a few hours earlier. Hudson returned his attention to the car, tomorrow’s interview being pushed to the back of his mind.

“It reminds me of where I grew up,” the girl said. Hudson heard her chair scrape on the floor as she scooted it back and walked in his direction. He expected her to stand next to him, but she settled in somewhere behind him, out of sight. “At the elementary school that I went to, there was this soccer field. It seems like nothing but an unkempt field of grass if you drive by it.” Hudson had to stop himself from turning around to watch her lips move as she spoke. “But every kid in Fredericksburg knows about the anthills. There’s two of them, one at each end of the field. One’s full of black ants and the other red. Every summer the soccer field gets overrun by this ant-on-ant war. I’m not sure if they’re territorial or they just happen to feed off each other, but it’s an incredible sight. All these little black and red things attacking each other, like watching thousands of checkers games being played from very far away. And it’s this little Fredericksburg treasure, just for us.”

Hudson caught himself smiling at the engine instead of replacing the spark plugs. “That’s great,” he said, the words feeling too flat. The girl hadn’t just let him ramble on; she’d known exactly what he meant. No one, not even Hudson’s dad, had ever understood him so perfectly.

There was a pause that Hudson didn’t know how to fill. He thought about asking her why the car was registered to an address in Louisiana instead of Texas, but it didn’t seem like the right time. He was thankful when the engine of the semi his dad had been working on started, and the truck began to maneuver its way out of the garage in a cacophonous series of back-up beeping and gear shifts.

When the truck had rumbled away down the street, Hudson turned around to look at the girl, but, feeling self-conscious under her gaze, he pretended to search for something on the shelves beside her. “When I’m done with your car, want to go on a treasure hunt?”

Hudson wasn’t sure where the question had come from, but he was glad he hadn’t paused to think about it, hadn’t given himself time to shy away from saying it out loud.

The question seemed to catch the girl off guard. “You want to show me around?” She glanced down at her feet, bare except for the red outline of her flip-flops.

“If you’re not busy, I mean.”

She seemed wary, which felt like an entirely reasonable thing for her to be. Hudson couldn’t believe he’d asked a stranger to go on a treasure hunt with him.

“Okay, sure,” she managed to say right before Hudson heard his dad enter the garage and call his name.

“Excuse me just one second,” he said to the girl, raising an apologetic hand as he sidestepped her. He resisted the urge to put a hand on her as he slid by so close, just a light touch on her lower back, on her shoulder, and joined his dad at the garage door.

“Hey, Pop,” Hudson said, putting his hands on his hips, mimicking his dad’s stance.

“Good day at school?”

“Yup. Nothing special. I did another mock interview with the counselor during lunch. Did pretty well, I think. That’s about it.”

His dad nodded a few times, then motioned toward the car. “What are you working on here?”

“General tune-up,” Hudson replied. “Filters, fluids, spark plugs. A new V-belt.”

“I can finish up for you. You should get some rest for tomorrow.”

“I’m almost done,” Hudson said, already sensing the discomfort he felt any time he had to ask his dad about something Hudson knew his dad wouldn’t approve of. “There’s just...” He looked back to see whether the girl was within earshot. “Well, this girl, she wants me to show her around town.” He waited to see if his dad would run a hand through his graying hair, his telltale sign of disapproval. “I promise I’ll be back for dinner,” Hudson added.

His dad glanced at his old Timex. “One hour,” he said, adding a reminder about how early Hudson would have to get up tomorrow to drive the fifty miles to the University of Mississippi campus in Jackson. “We don’t want you to be too tired.”

“I won’t be, I promise,” he said, tiny fantasies of the next hour with the girl already flooding his head. The back of their hands grazing against each other—not entirely by accident—as they walked; her leg resting against his as they sat somewhere together, getting to know each other. Already racking his mind for places where he could take her, Hudson thanked his dad with a quick hug and then went back to the front of the car. The girl had a hand resting on the hood, staring vaguely at the engine block. “I just have a couple more things to do, and then we can get going,” he said.

“Great.” Her lips spread into a warm, genuine smile, and she held out her hand. “By the way, I’m Leila.”

He wiped his hand off on his work pants and said his name as he shook her hand. Months, he thought to himself, his fingers practically buzzing at the touch of her skin. I’ll be thinking about her for months.

2 (#ulink_7a10cec3-046c-5186-bec5-a919614f8835)

AFTER HE WAS done fixing Leila’s car, Hudson went to the back of the shop to change out of his work clothes while Leila settled the bill with his dad. When he came out, he saw her sitting in the front passenger seat of her idling car.

“I’m driving?” he asked as he opened the driver-side door.

“You’re the tour guide,” she said, making a sweeping gesture with her arm as if to indicate that the world beyond the windshield was vast and unexplored. “Guide me.”

She smiled at him, and he thought to himself that she was exceptionally good at smiling. He shifted the car into drive and pulled out onto the street, wondering where to take her, how to get her to smile more often. The obvious treasure was the oxbow, but it was too far away. Everything that was nearby held fond memories—the Coca-Cola museum he’d gone to on every birthday until he was twelve, the ice cream shop that invited its customers to suggest new, strange flavors and had once taken up Hudson’s request for Bacon Chocolate—but the only way to transplant memories onto places and make them feel like treasures to her was to talk. He usually didn’t have trouble talking to girls, even beautiful ones, but while he didn’t quite feel tongue-tied around her, he didn’t know how to begin. “It’s very red in here,” he said at last.