По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

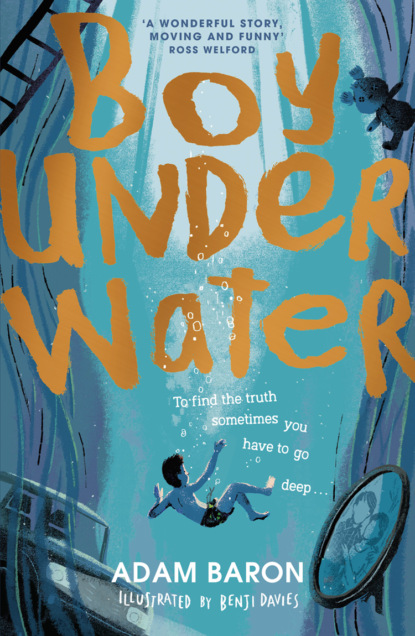

Boy Underwater

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Uncle Bill took a breath. ‘Maybe later. I’m not sure. After school. Perhaps. I have to find out, Cym, okay?’

Okay?! That was the last word I was going to agree with. How could he possibly ask me if anything was okay? I didn’t argue, though. I just shrugged and went to get dressed. When I was done we left the house and Uncle Bill turned to me.

‘How do you normally get to school?’

‘Taxi,’ I said, though this time he wasn’t buying it and he took me off to the bus stop.

It’s weird. Yesterday, the worst, most terrible and embarrassing thing in the HISTORY OF THE WORLD had happened. But, as we got off the bus and walked across the heath to my school, it was nowhere. I wasn’t thinking about it. I’d been pushed into a swimming pool. The entire class had seen me without anything on. And that wasn’t everything. Oh no, it actually got much worse. We hadn’t just gone back to school after the pool. Instead Miss Phillips had called my mum to come and get me. Mum cycled to the pool from Messy Art and went nuclear. Everyone stared in amazement as she screamed at Miss Phillips and the man in the red polo shirt for not looking after me properly. She glared at the kids, demanding to know who had pushed me in. Billy Lee went white as paper. I just stood there, aware that this would be news for weeks, months, even forever, a school legend that would be passed on from year to year until, eventually, my own children would run home from school and tell me all about THE NUDE KID WITH THE CRAZY MUM. But now I didn’t care. There was a huge hollowness deep inside me that made everything else seem trivial. My. Mum. Was. Gone. She’d never gone, not ever. It was her and me, always. I felt empty, sucked out, and when I saw Lance pushing his bike in through the school gates I realised something else. He’d asked me a simple question about swimming and I’d lied to him. I’d said I was really good. Because of that I’d ended up at the bottom of the swimming pool and because of that, my mum had somehow got ill. So ill she’d had to go to the hospital.

So it was all my fault.

Uncle Bill started to say goodbye but I shook my head.

‘I’m not going in. I’m going to see my mum.’

‘Cym …’

‘I’m going to see my mum,’ I said again. ‘And nothing’s going to stop me.’

At that, Uncle Bill sighed and he did this open-mouthed thinking thing. Then he made some calls, said ‘thank you’ a lot, and I knew he was talking to work. Uncle Bill is the head of a charity that looks after vulnareb … vulnorib … vulenerob … people who need help. He’s like super busy doing that but he seemed to have sorted things out as he gave me a thumbs-up, before going into his phone again. This next conversation didn’t go as well. He got a bit cross and, even though he turned away from me, I heard him say things like, ‘We both have to help,’ and, ‘Last time, you didn’t do a thing, did you?’ But eventually he seemed to have sorted out whatever it was and he put his arm round my shoulder.

‘Come on then,’ he said. We walked up the little hill from school and I pretended not to see Veronique Chang getting out of her mum’s Volvo.

‘Cymbeline!’ she called out.

‘Cym?’ Uncle Bill said, when I ignored Veronique. ‘Aren’t you going to …?’

‘Not me,’ I said. ‘Different boy. There’s a Cymbeline in Year Five.’

‘Oh,’ Uncle Bill said, and we walked off to the train station.

(#ulink_040fc358-58b0-554a-aae3-1356a10481e5)

It didn’t take long. Four stops from Blackheath to somewhere called Welling. Good name for a place with a hospital, I thought. We got off the train and walked down this long high street past a Cancer Research and a Mencap. Mum would probably have dragged me into both of them. We’re always going in charity shops, for books and coats and stuff. Christmas cards in January, because she likes to be prepared. Last summer she bought this dress from the Oxfam in Blackheath Village. She loved it and was all smiley when she wore it, though on the heath after school one day Billy Lee’s mum told her that she had one just like it.

‘Well, I used to have,’ she said. And then she did this loud sniggering laugh, and Mum went red. She doesn’t wear it any more.

After going past a Greggs that smelled of sausage rolls we turned into some side streets. Uncle Bill didn’t need a map or anything and that made me frown.

‘Have you been here before?’

Uncle Bill looked annoyed with himself. I don’t think he meant to give that away.

‘You have, haven’t you?’

‘Yes.’

‘To see my mum?’ He nodded. ‘Has she been in this hospital before?’ He nodded again and I nodded back. It probably happened in that weird time Mum sometimes speaks about: BEFORE YOU WERE BORN. An odd time that, interesting in a way, though not particularly relevant to anything. ‘Before I was …?’

‘No, Cym. When you were a baby.’

‘And Mum went into hospital? Who looked after me?’

‘I did.’

‘Oh,’ I said, and my insides felt strange. It was shaky to hear that Mum had been in hospital before, but knowing Uncle Bill had looked after me made me feel shy, and warm inside. I put my hand in his and he squeezed it.

‘Did I visit her?’

‘I took you every day.’

‘So was she in there for quite a while? How long’s she going to be in this time?’ I had a terrible thought. ‘She WILL be out for my birthday, won’t she?’

Uncle Bill looked caught out again and, suddenly, very serious. But he answered with nothing more than a shrug, and led me down some more side streets until we were walking towards the gates of a soggy-looking park.

‘Wait,’ I said, before we got there.

There was a greengrocer’s outside the park with fruit all piled up. There were flowers too, in a bucket. I led Uncle Bill towards it and picked some – red ones, Mum’s favourite colour. Uncle Bill handed them to the lady and she put paper round them. Bill gave her a fiver, which I said I’d give him back from my money box, and he gave them to me to hold. We walked into the park and I saw some swings and a duck pond, and an old-looking building over on the far side. When Uncle Bill looked at it I knew that was where we were going and I had a picture of Mum in her bed, with lots of other ladies in a row. She’d have her favourite nightie on and a bandage round her head for the headache. Mum would sit up, beaming, when she saw me. We’d put the flowers in a vase. The first thing she’d say was of course she’d be out by Saturday. I’d get my spellings out and we’d go through them like we always did on Tuesday mornings and Mum would try not to giggle at some of the answers I gave. She’d tell the other ladies I was her little champion. She’d kiss me and I’d say, ‘Get well soon,’ and then I’d be really careful not to hurt her head when I hugged her goodbye. She’d wave at me through the window when we left – her special boy.

The picture cheered me up and I told myself off. This wouldn’t be so bad. Mums went into hospital all the time. Lance’s did last year. His new-dad came to get him from school and when he came back next day his mum had had a baby.

‘So you’ve got a sister?’

‘A half-sister.’

‘Which half is your sister?’

‘The top,’ he said. ‘Definitely.’

I started to glow inside at the thought of seeing Mum and I pulled Bill to go faster. We got to the building, which was made out of dark red bricks that were black round the edges. We stood in front of a heavy blue door until a buzzer sounded and the door clicked open. We walked into a really bright reception and up to a big desk with two nurses behind it, one of them typing on a computer. The other left us standing there for a few minutes as she wrote something. Then, without looking up, she asked how she could help.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: