Rollo on the Rhine

"Yes," said Mr. George, "it would grow very well, but the land is too valuable to appropriate it to such a purpose. The whole country below Cologne, where we came to the river, is smooth and level, and free from stones, so that it is easily ploughed and tilled; and thus grain, and flax, and other very valuable crops can be raised upon it. They raise a few trees in that part of the country, but not many."

"I never heard of raising trees before," said Rollo, "except apple trees, or something like that."

"True," said Mr. George, "because in America, as that is a new country, there is an abundance of native forests, where the trees grow wild. But you must remember that every foot of land in Europe has been in the possession of man, and occupied by him, for two thousand years. There is not a field or a hill, or even a rocky steep on the mountain side, which has not had sixty or seventy generations of owners, who have all been watching it, and taking care of it, and improving it more or less all that time; each one carefully considering what his land can produce most profitably, and taking care of it and managing it especially with reference to that production. If his land is smooth and level, he ploughs it, and cultivates it for grass, or grain, or other plants requiring special tillage. If it is in steep slopes, with a warm exposure, he terraces it up, and makes vineyards of it. If it is in steep slopes, with a cold exposure, then it will do for timber, provided there are streams near it, so that he can float the timber away. If there are no streams near it, he can use it as pasture ground for sheep or cattle; for the wool, or the butter and cheese, which he obtains from this kind of farming, can be transported without streams; or, at least, such commodities will bear transporting farther before coming to a stream than wood or timber. Thus, you see, whatever the land is fit for, it has been appropriated to for a great many centuries; and it has all been cropped over and over again, even where the crop is a forest of trees. If we allow the trees even a hundred years to grow, before they are large enough to cut, that would give, in two thousand years, time to cut them off and let them grow up again twenty times."

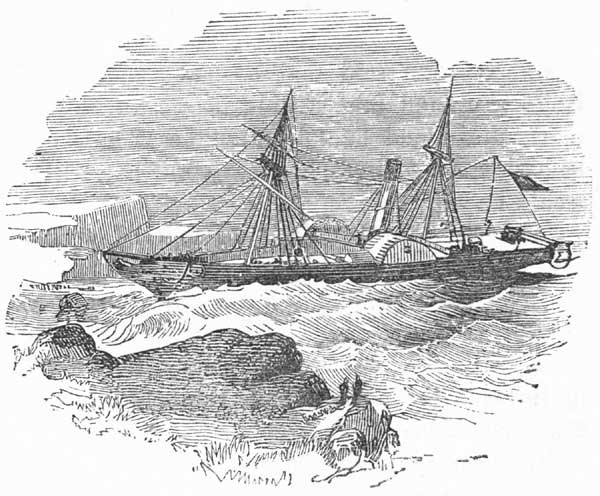

"Here comes a steamer," said Rollo.

Just then the bow of a steamer came shooting into view, down the river. On the forward part of the deck were several soldiers and laborers, with women and children that looked like emigrants, and also a huge pile of trunks and merchandise covered with a tarpauling. Then came the paddle wheels, and then the quarter deck, with a large company of tourists, most of whom were looking about very eagerly at the scenery, with guide books and glasses in their hands. These were tourists that had been travelling in Switzerland, and were coming home by way of the Rhine; and as they were now just entering the part of the river where the grand and imposing scenery was to be seen,—though Mr. George and Rollo were just leaving it,—they were full of wonder and admiration at the various objects which appeared around them on every side. Rollo had but a very brief opportunity to look at these strangers, for the steamer which conveyed them passed by very swiftly, and in a moment they were gone.

"How swift!" said Rollo.

"Yes," said Mr. George, "they go down the stream much faster than they go up; for in going down they have the current to help them, but we have it to hinder us in going up."

"And does it help just as much as it hinders?" asked Rollo.

"Yes," said Mr. George, "for any given time. If the current flows two miles an hour, it will carry forward a boat that is going with it just two miles faster than it would go in still water. And if the boat is going against it, it will go just two miles an hour slower.

"Thus, you see," continued Mr. George, "if a steamer had an engine capable of driving her twelve miles an hour through the water, in navigating a stream that flows two miles an hour, she would go fourteen miles an hour in going down, and ten miles an hour in going up."

"Then," said Rollo, "it seems that the help of a current is just as much as the hinderance of it, and that a river running fast is just as good for navigation as if the water were still. Because, you see," he added, "that though they lose some headway in going up, they gain it just the same in coming down."

"That reasoning seems plausible," replied Mr. George, "but it is not sound."

"What do you mean by plausible?" asked Rollo.

"Why, it appears to be good, when it really is not so. Reasoning very often appears to be good, while there is all the time some latent flaw in it which makes the conclusion wrong. Very often something is left out of the account which ought to be taken in and calculated for, and that is the case here. The truth is, that the current helps the steamer in going down just as much as it retards her in coming up for any given time; as for instance, for an hour, or for six hours. But we are to consider that in accomplishing any given distance, the steamer is longer in coming up than she is in going down, and so is exposed to the retarding effect of the current longer than she has the benefit of its coöperation.

"For example," continued Mr. George, "suppose the distance from one place to another, on a river flowing two miles an hour, is such that it takes a steamer three hours to go down and four hours to come up. In going down she would be aided how much?"

"Two miles an hour," said Rollo.

"And that makes how much for the whole time going down?" asked Mr. George.

"Six miles," said Rollo.

"Now, it takes her four hours to go up," said Mr. George. "How much would she be kept back then by the current?"

"Why, two miles an hour for four hours," said Rollo, "which would make eight miles."

"Thus in the double voyage," said Mr. George, "the boat would be helped six miles and hindered eight, so that the current would on the whole be a serious disadvantage. For a steamer, therefore, which is to be navigated equally both ways, the current is an evil.

"But for that sort of navigation which goes only one way, it is a great advantage. For instance, the rafts have to come down, but they never have to go back again; and so they have the whole advantage of the current in bringing them down, without any disadvantage to balance it.

"On the whole," said Mr. George, "I do not see but that the currents of great rivers are an advantage, for there is always a much greater quantity to come down than to go up. The heavy products that grow on the borders of the rivers are to come down, while comparatively little in quantity goes up. So the benefit, on the whole, which is produced by the flow of the water, may be greater than the injury."

"What do they do with the rafts," said Rollo, "when they get them down the river?"

"They break them up," said Mr. George, "and sell the timber in the countries near the mouth of the river, where but little timber grows."

By this time, Mr. George and Rollo had finished eating the meats which they had ordered for their dinner, and so the waiter came and took away the plates, and brought the omelet and the coffee. With the coffee the waiter brought two small plates and knives, and some very nice rolls and butter. He also brought a plate containing several slices of a kind of cake, toasted. This cake was very nice.

While Rollo was eating it he asked his uncle George whether, in case he had gone down the river to Boppard, and had not got back until dark, he should not have been anxious about him.

"No," said Mr. George, "not much. I took precautions against that."

"What precautions?" asked Rollo.

"Why, I sent a man with you to take care of you," said Mr. George.

"You sent a man with me?" repeated Rollo, very much surprised.

"Yes," said Mr. George, quietly. "As soon as you had gone out of my room, to go on board the raft, I called the waiter, and asked him to send a commissioner with you, to see that you did not get into any difficulty, and to take care of you in case there should be any occasion."

"Now, uncle George," said Rollo, in a mournful and complaining tone, "that was not fair."

"Why not?" asked Mr. George.

"Because," said Rollo, "I wanted to take care of myself."

"Well," said Mr. George, "you did take care of yourself—didn't you? My plan did not interfere with yours at all—did it?"

Rollo did not answer, but he looked as if he were not convinced.

"I gave the man special charge," said Mr. George, "not to interfere with you in any way, and not even to let you know that I had said any thing about you to him, so that you should be left entirely to your own resources. And you were so left. You acted in the whole affair just as you thought proper, and took care of yourself admirably well. I think especially that you were very wise in leaving the raft when you did, instead of remaining on board three or four hours longer. But however this may be, you acted for yourself throughout. I did not interfere with you at all."

"Well," said Rollo, after a moment's pause, "what you say is very true. But it seems to me it was a little artful in you to do that; and you always tell me that I must not be artful, but must be perfectly honest and open in all that I do. Don't you think you deceived me a little?"

"I do not see that I did," said Mr. George. "When we deceive a person, we do it by saying or doing something to give him a false impression, or to make him suppose that something is true which is not true. Now, what did I do or say to give you any false impression?"

"Why, nothing, I suppose," said Rollo, "except sending that man to take care of me without letting me know it."

"That was concealing something from you," said Mr. George, "not deceiving you. There are a thousand occasions when it is right to conceal things from the people around us. That is very different from deceiving them. This was a case in which I thought it best to conceal what I did, for a time, though I intended to tell you in the end. You see, I should not have done my duty, as a guardian intrusted with the care of a boy by his father, if I had allowed you to go away from me on such a doubtful expedition without some precautions. So I thought it best to send the commissioner; but I knew you wished to take care of yourself, and so I charged the commissioner to allow you to do so, and on no account to interpose, unless some accident, or unforeseen emergency, should occur. I told him not even to let you know that he was there, so that you might not be embarrassed or restricted at all by his presence, or even relieved of any portion of your solicitude. But I determined to tell you all about it as soon as it was over, and I was fondly imagining that you would praise me for my sagacity in managing the business as I did, and also especially for my openness and honesty in explaining all to you at last. But instead of that, it seems you think I did wrong; so that where I expected compliments and praise, I get only censure and condemnation; and I do not know what I shall do."

Mr. George said this with a perfectly grave face, and with such a tone of mock meekness and despondency, that Rollo burst into a loud laugh.

"If you could think of any suitable punishment for me," continued Mr. George, in the same penitent tone, "I would submit to it very contentedly; though I do not see myself any suitable way by which I can be punished, except perhaps by a fine."

"Yes," said Rollo, "a fine; you shall be fined, uncle George. There is a woman out here that has got some raspberries, in little paper baskets. You shall be fined a paper of raspberries."

Mr. George acceded to this proposal. The raspberries were two groschen a basket. Mr. George gave Rollo the money, and Rollo, going forward with it, bought the raspberries, and he and Mr. George ate them up together. They served the double purpose of a punishment for the offence, and of a dessert for the dinner.

Chapter XIII.

Bingen

At some places on the Rhine the passengers go on board the steamers and land from them in a small boat, as Mr. George and Rollo did at St. Goar. At others there is a regular pier for a landing. At all the large towns there is a pier,—in some there are two or three,—which belong severally to the different companies which own the lines of steamers. These piers are constructed in a very peculiar manner. They are made by means of a large and heavy boat, which is anchored at a short distance from the shore, and then a massive platform is built, extending from the quay to this boat. The boat, being afloat, rises and falls with the river; and thus the end of the platform which rests upon it is kept always at the proper level for the landing of the passengers, so that, whatever may be the state of the water, they go over on a level plank. This is a very convenient arrangement for such a river as the Rhine, which rises and falls considerably at different seasons, on account of the variation in the quantity of rain, and in the melting of the snows, on the mountains in Switzerland.

Bingen is one of the towns where there is a floating pier of this kind, and Mr. George and Rollo were safely landed upon it about eight o'clock. It was a very pleasant evening. As they approached the town, before they landed, they both walked forward towards the bows of the vessel, to see what sort of a place it was where they were going to spend the night.

"It is just like Coblenz," said Mr. George, "only on a small scale."

It was indeed very much like Coblenz in its situation, for it was built on a point of land formed between the Rhine and the Nahe, a branch which came in here from the westward, just as Coblenz was at the junction of the Rhine and the Moselle. There was a bridge across the Moselle, you recollect, just at the mouth of it, on the lower side of the town, which bridge was made to accommodate the travellers going up and down the Rhine on that side. There was just such a bridge across the mouth of the Nahe. So that the situation of the town was in all respects very similar to that of Coblenz.

Just below the town there was a small green island covered with shrubbery, and on the upper end of the island was a high, square tower, standing alone.

"That's must be Bishop Hatto's Tower," said Mr. George.

"Who was he?" asked Rollo.

"He was a man that was eaten up by the rats," said Mr. George, "because he called the poor people rats, and burned up a great many of them in his barn. The story is in the guide book. I will read it to you when we get to the hotel."

By this time the boat had glided by the island, and the tower was out of view; and very soon afterwards Mr. George and Rollo were landed on the floating pier, as I have already said. There were very few people to land, and the boat seemed merely to touch the pier and then to glide away again.

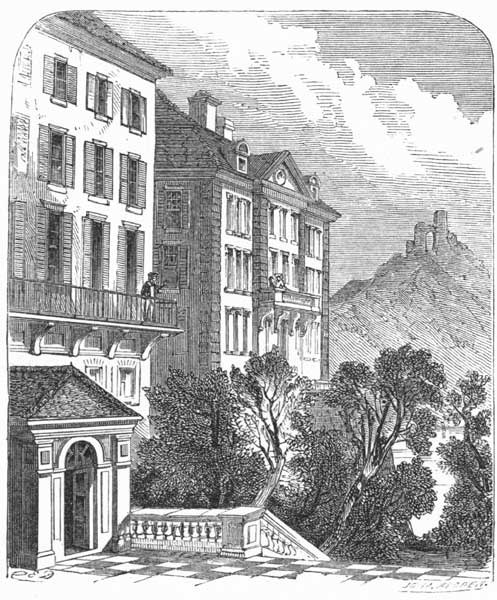

There were several porters standing by, and they immediately took up the passengers' baggage, and carried it away to the hotels, which were all very near the river. Rollo and Mr. George were soon comfortably established in a room with two beds in it, one in each corner, and a large round table near one of the windows. Outside of the other window was a balcony, and Rollo immediately went out there, to look at the view.

"We have not got quite out yet, uncle George," said he.

Rollo was right, for the bank of the river opposite Bingen was very steep and high, and was terraced from top to bottom for vineyards. In fact, this part of the river is more celebrated, perhaps, than any other for the excellent quality of the grapes which it produces. It is here that are situated the famous vineyards of Rudesheim and Johannisberg. In fact, the whole country, for miles in extent, is one vast vineyard. The separate fields are divided from one another by the terrace walls, which run parallel to the river, and by paths formed sometimes by steps, and sometimes by zigzags, which ascend and descend from the crest of the hills above to the line of the shore. The only buildings to be seen among all this vast expanse of walls and terraces are the little watchtowers that are erected here and there at commanding points to enable the vinegrowers to watch the fruit, when it comes to the time of ripening. The laborers who till the fields, and dress the vines, and gather the grapes in the season, live all of them in compact villages, built at intervals along the shore.

While Rollo was looking at this scene, and wondering how such an immense number of walls and terraces could ever have been built, his attention was suddenly arrested by hearing a sweet and silvery voice, like that of a girl, calling out,—

"Rollo."

Rollo turned in the direction of the sound, and found that it was Minnie speaking to him. She was standing on another balcony, one which opened from the chamber next to his. Rollo was very much pleased to see her. He thought it very remarkable that he should meet her thus so many times; but it was not. Travellers on the Rhine going in the same direction, and stopping to see the same things, often meet each other in this way again and again.

After talking with Minnie some little time from the balcony, Rollo asked her if her mother was there.

"Yes," said Minnie.

"Ask her then," said Rollo, "if you may come down and take a walk with me in the garden."

Minnie went in from the balcony, and in a moment returning, she said, "Yes," and immediately disappeared again. So Rollo went down, and Minnie presently came and met him in the garden.

MINNIE.

The garden was a small piece of ground in front of the hotel, between the hotel and the river. There was a large gate opening from it towards the hotel, and another towards the river. The garden was full of shade trees, with pleasant walks winding about among them, and here and there a border, or a bed of flowers. There were several carved images placed here and there, one of which amused Rollo and Minnie very much, for it represented a monkey sitting on a pole and looking at himself in a hand looking glass which he held before his face. In the other hand he had a parasol.

In the front part of the garden, towards the river, were several tables under the trees, where people might take coffee or ices, or they might take their dinner there if they chose. In the front of the garden too, at the corners, were two summer houses, with tables and chairs in them. The sides of these houses that were turned towards the river, and also those that were towards the gardens, were open. The other two sides of each summer house had walls, on which were painted views of castles and other scenery of the Rhine. Over one of the summer houses was a little room for a lookout, where there was a very fine prospect up and down the river.

Rollo and Minnie rambled about here for some time, examining every thing with great attention. They chose one of the pleasantest tables, and sat down before it.

"This is a nice place," said Minnie. "I propose that you and I come out here to-morrow morning and have breakfast, all by ourselves."

"O, we can't do that very well," said Rollo.

"Yes we can," replied Minnie, "just as well as not. I'll plan it all."

Minnie then jumped up and led the way, Rollo following, through the open gate towards the river. There was a sort of street outside, and Rollo and Minnie stood here for a few minutes to see a steamer go by. Minnie then proposed that they should get into a boat that was lying there, and take a sail.

"You can row—can't you?" said she to Rollo.

"No," said Rollo, "not on such a river as this. See how swift the current flows."

"Never mind," said Minnie, "I can. Let us jump into this boat, and have a sail."

"No," said Rollo, "not for the world. We should be carried off down the stream in spite of every thing."

"Never mind," said Minnie; "we should land somewhere, and they would send down for us. We should have a great deal of fun."

How far Minnie would have persevered in urging her plan for a venture in the boat on the river I do not know; but the conversation was here interrupted by the appearance of Mr. George, who had come down through the garden, and just at this instant joined the children on the quay.

Chapter XIV.

The Ruin in the Garden

Mr. George said that he had come to ask Rollo to go and take a walk to see an old ruin in the town, and he told Minnie that he should be very glad to have her go too, if her mother would be willing.

"O, yes," said Minnie, "she will be willing. I'll go."

"You must go and ask her first," said Mr. George.

So, while Mr. George and Rollo walked slowly up towards the hotel, Minnie ran before them to ask her mother.

Mr. George explained to Rollo in walking through the garden, that there were two ruins that he wished to see while he was at Bingen. One was the famous castle of Rheinstein, which stood on the bank of the river, a few miles below the town.

"But it is too late to go there to-night," said Mr. George. "We will take that for to-morrow. But there is an old ruin back here in the village, which I think we can see to-night."

When they reached the door of the hotel, Minnie met them, and said that she could go; and so they walked along together.

Mr. George groped about a long time among the narrow streets and passage ways of the town, to find some way of access to the ruin, but in vain. He obtained frequent views of it, and of the rocky hill that it stood upon, which was seen here and there, by chance glimpses, rising in massive grandeur above the houses of the town; but he could not find any way to get to it.

"It is in a private garden," said Mr. George, "I know; but how to find the way to it I cannot imagine."

"Perhaps it is here," said Minnie.

So saying, Minnie ran up to a gate by the side of the street, which led into a very pretty yard, all shaded with trees and shrubbery, and having a large and handsome house by the side of it. The gate was shut and fastened, but Minnie could look through the bars.

There was a woman standing near one of the doors of the house, and Minnie beckoned to her. The woman came immediately down towards the gate. Minnie pointed in towards a walk which seemed to lead back among the trees, and said to the woman,—

"Schloss?"

Schloss is the German word for castle. Minnie could not speak German; but she knew some words of that language, and the words that she did know she was always perfectly ready to use, whenever an occasion presented.

"Ja, Ja," said the woman; and immediately she opened the gate. By this time Minnie had beckoned Mr. George and Rollo to come up from the road, and they all three went in through the gate.

The woman called to a man who was then just coming down out of the garden, and said something to him in German. None of our party could understand what she said; but they knew from the circumstances of the case, and from her actions, that she was saying to him that the strangers wished to see the ruins. So, the man leading the way, and the three visitors following him, they all went on along a broad gravel walk which led up into the garden.

Mr. George asked the guide if he could speak English, and he said, "Nein." Then he asked him if he could speak French, and he said, "Nein." He said he could only speak German.

"He can't explain any thing to us, children," said Mr. George; "we shall have to judge for ourselves."

The walk was very shady that led along the garden, and as it was now long past eight o'clock, it was nearly dark walking there, though it was still pretty light under the open sky. The walk gradually ascended, and it soon brought the party to a place where they could see, rising up among the trees, fragments of ancient walls of stupendous height. Rollo looked up to them with wonder. He even felt a degree of awe, as well as wonder, for the strange and uncouth forms of windows and doors, which were seen here and there; the embrasures, and the yawning arches which appeared below, leading apparently to subterranean dungeons, being all dimly seen in the obscurity of the night, suggested to his mind ideas of prisoners confined there in ancient times, and wearing out their lives in a dreadful and hopeless captivity, or being put to death by horrid tortures.