Rollo on the Atlantic

So Rollo began to make preparations for a removal. He threw the bolster and pillows across first, and then, getting out of the berth, and holding firmly to the edge of it, he waited for a moment's pause in the motion of the ship; and then, when he thought that the right time had come, he ran across. It happened, however, that he made a miscalculation as to the time; for the ship was then just beginning to careen violently in the direction in which he was going, and thus he was pitched head foremost over into the couch, where he floundered about several minutes among the pillows and bolsters before he could recover the command of himself.

At last he lay down, and attempted to compose himself to sleep; but he soon experienced a new trouble. It happened that there were some cloaks and coats hanging up upon a brass hook above him, and, as the ship rolled from side to side, the lower ends of them were continually swinging to and fro, directly over Rollo's face. He tried for a time to get out of the way of them, by moving his head one way and the other; but they seemed to follow him wherever he went, and so he was obliged at last to climb up and take them all off the hook, and throw them away into a corner. Then he lay down again, thinking that he should now be able to rest in peace.

At length, when he became finally settled, and began to think at last that perhaps he should be able to go to sleep, he thought that he heard something rolling about in Jennie's state room, and also, at intervals, a mewing sound. He listened. The door between the two state rooms was always put open a little way every night, and secured so by the chambermaid, so that either of the children might call to the other if any thing were wanted. It was thus that Rollo heard the sound that came from Jennie's room. After listening a moment, he heard Jennie's voice calling to him.

"Rollo," said she, "are you awake?"

"Yes," said Rollo.

"Then I wish you would come and help my kitten. Here she is, shut up in her cage, and rolling in it all about the room."

It was even so. Jennie had put Tiger into the cage at night when she went to bed, as she was accustomed to do, and then had set the cage in the corner of the state room. The violent motion of the ship had upset the cage, and it was now rolling about from one side of the state room to the other—the poor kitten mewing piteously all the time, and wondering what could be the cause of the astonishing gyrations that she was undergoing. Maria was asleep all the time, and heard nothing of it all.

Rollo said he would get up and help the kitten. So he disengaged himself from the wedgings of pillows and bolsters in which he had been packed, and, clinging all the time to something for support, he made his way into Jennie's state room. There was a dim light shining there, which came through a pane of glass on one side of the state room, near the door. This light was not sufficient to enable Rollo to see any thing very distinctly. He however at length succeeded, by holding to the side of Jennie's berth with one hand, while he groped about the floor with the other, in finding the cage and securing it.

"I've got it," said Rollo, holding it up to the light. "It is the cage, and Tiger is in it. Poor thing! she looks frightened half to death. Would you let her out?"

"O, no," said Jennie. "She'll only be rolled about the rooms herself."

"Why, she could hold on with her claws, I should think," said Rollo.

"No," said Jennie, "keep her in the cage, and put the cage in some safe place where it can't get away."

So Rollo put the kitten into the cage, and then put the cage itself in a narrow space between the foot of the couch and the end of the state room, where he wedged it in safely with a carpet bag. Having done this, he was just about returning to his place, when he was dreadfully alarmed at the sound of a terrible concussion upon the side of the ship, succeeded by a noise as of something breaking open in his state room, and a rush of water which seemed to come pouring in there like a torrent, and falling on the floor. Rollo's first thought was that the ship had sprung a leak, and that she was filling with water, and would sink immediately. Jennie, too, was exceedingly alarmed; while Maria, who had been sound asleep all this time, started up suddenly in great terror, calling out,—

"Mercy on me! what's that?"

"I'm sure I don't know," said Rollo, "unless the ship is sinking."

Maria put out her hand and rung the bell violently. In the mean time, the noise that had so alarmed the children ceased, and nothing was heard in Rollo's room but a sort of washing sound, as of water dashed to and fro on the floor. Of course, the excessive fears which the children had felt at first were in a great measure allayed.

In a moment the chambermaid came in with a light in her hand, and asked what was the matter.

"I don't know," said Maria. "Something or other has happened in Rollo's state room. Please look in and see."

The chambermaid went in, and exclaimed, as she entered,—

"What a goose!"

"Who's a goose?" said Rollo, following her.

"I am," said the chambermaid, "for forgetting to screw up your light. But go back; you'll get wet, if you come here."

Rollo accordingly kept back in Jennie's state room, though he advanced as near to the door as he could, and looked in to see what had happened. He found that his little round window had been burst open by a heavy sea, and that a great quantity of water had rushed in. His couch, which was directly under the window, was completely drenched, and so was the floor; though most of the water, except that which was retained by the bedding and the carpet, had run off through some unseen opening below. When Rollo got where he could see, the chambermaid was busy screwing up his window tight into its place. It has already been explained that this window was formed of one small and very thick pane of glass, of an oval form, and set in an iron frame, which was attached by a hinge on one side, and made to be secured when it was shut by a strong screw and clamp on the other.

"There," said the chambermaid. "It is safe now; only you can't sleep upon the couch any more, it is so wet. You must get into your berth again. I will make you up a new bed on the couch in the morning."

Rollo accordingly clambered up into his berth again, and the chambermaid left him to himself. Presently, however, she came back with a dry pillow and bolster for him.

"What makes the ship pitch and toss about so?" said Rollo.

"Head wind and a heavy sea," said the chambermaid; "that's all."

The chambermaid then, bidding Rollo go to sleep, passed on into Jennie's state room, on her way to her own place of repose. As she went by, Maria asked if there was not a storm coming on.

"Yes," said the chambermaid, "a terrible storm."

"How long will it be before morning?" asked Jennie.

"O, it is not two bells yet," said the chambermaid. "And you had better not get up when the morning comes. You'll only be knocking about the cabins if you do. I'll bring you some breakfast when it is time."

So saying, the chambermaid went away, and, left the children and Maria to themselves.

Rollo tried for a long time after this to get to sleep, but all was in vain. He heard two bells strike, and then three, and then four. He turned over first one way, and then the other; his head aching, and his limbs cramped and benumbed from the confined and uncomfortable positions in which he was obliged to keep them. In fact, when Jennie on one occasion, just after four bells struck, being very restless and wakeful herself, ventured to speak to him in a gentle tone, and ask him whether he was asleep, he replied that he was not; that he had been trying very hard, but he could not get any thing of him asleep except his legs.

At length the gray light of the morning began to shine in at his little round window. This he was very glad to see, although it did not promise any decided relief to his misery; for the storm still continued with unabated violence. At length, when breakfast time came, the chambermaid brought in some tea and toast for Maria and for both the children. They took it, and felt much better for it—so much so, that Rollo said he meant to get up and go and see the storm.

"Well," said the chambermaid, "you may go, if you must. Dress yourself, and go on the next deck above this, and walk along the passage way that leads aft, and there you'll find a door that you can open and look out. You'll be safe there."

"Which way is aft?" asked Rollo.

"That way," replied the chambermaid, pointing.

So Rollo got up, and holding firmly to the side of his berth with one hand, and bracing himself between his berth and the side of his wash stand cupboard with his knees, as the ship lurched to and fro, he contrived to dress himself, though he was a long time in accomplishing the feat. He then told Jennie that he was going up stairs to look out at some window or door, in order to see the storm. Jennie did not make much reply, and so Rollo went away.

The ship rolled and pitched so violently that he could not stand alone for an instant. If he attempted to do so, he would be thrown against one side or the other of the cabin or passage way by the most sudden and unaccountable impulses. He finally succeeded in getting up upon the main deck, where he went into the enclosed space which has already been described. This space was closely shut up now on all sides. There were, however, two doors which led from it out upon the deck. In order to go up upon the promenade deck, it was necessary to go out at one of these doors, and then ascend the promenade deck stairway. Rollo had, however, no intention of doing this, though he thought that perhaps he might open one of the doors a little and look out.

While he was thinking of this, he heard steps behind him as of some one coming up stairs, and then a voice, saying,—

"Halloo, Rollo! Are you up here?"

Rollo turned round and saw Hilbert. He was clinging to the side of the doorway. Rollo himself was upon one of the settees.

Just then one of the outer doors opened, and a man came in. He was an officer of the ship. A terrible gust of wind came in with him. The officer closed the door again immediately, and seeing the boys, he said to them,—

"Well, boys, you are pretty good sailors, to be about the ship such weather as this."

"I'm going up on the promenade deck," said Hilbert.

"No," said the officer, "you had better do no such thing. You will get pitched into the lee scuppers before you know where you are."

"Is there any place where we can look out and see the sea?" said Rollo.

"Yes," replied the officer; "go aft, there, along that passage way, and you will find a door on the lee quarter where you can look out."

So saying, the officer went away down into the cabin.

Hilbert did not know what was meant by getting pitched into the lee scuppers, and Rollo did not know what the lee quarter could be. He however determined to go in the direction that the man had indicated, and see if he could find the door.

As for Hilbert, he said to Rollo that he was not afraid of the lee scuppers or any other scuppers, and he was going up on the promenade deck. There was an iron railing, he said, that he could cling to all the way.

Rollo, in the mean time, went along the passage way, bracing his arms against the sides of it as he advanced. The ship was rolling over from side to side so excessively that he was borne with his whole weight first against one side of the passage way, and then against the other, so heavily that he was every moment obliged to stop and wait until the ship came up again before he could go on. At length he came into a small room with several doors opening from it. In the back side of this room was the compartment where the helmsman stood with his wheel. There were several men in this place with the helmsman, helping him to control the wheel. Rollo observed, too, that there were a number of large rockets put away in a sort of frame in the coil overhead.

He went to one of the doors that was on the right-hand side of this room, and opened it a little way; but the wind and rain came in so violently that he thought he would go to the opposite side and try that door. This idea proved a very fortunate one, for, being now on the sheltered side of the ship, he could open the door and look out without exposing himself to the fury of the storm. He gazed for a time at the raging fury of the sea with a sentiment of profound admiration and awe. The surface of the ocean was covered with foam, and the waves were tossing themselves up in prodigious heaps; the crests, as fast as they were formed, being seized and hurled away by the wind in a mass of driving spray, which went scudding over the water like drifting snow in a wintry storm on land.

After Rollo had looked upon this scene until he was satisfied, he shut the door, and returned along the passage way, intending to go down and give Jennie an account of his adventures. As he advanced toward the little compartment where the landing was, from the stairs, he heard a sound as of some one in distress, and on drawing near he found Hilbert coming in perfectly drenched with sea water. He was moaning and crying bitterly, and, as he staggered along, the water dripped from his clothes in streams. Rollo asked him what was the matter; but he could get no answer. Hilbert pressed on sullenly, crying and groaning as he went down to find his father.

The matter was, that, in attempting to go up on the promenade deck, he had unfortunately taken the stairway on the weather side; and when he had got half way up, a terrible sea struck the ship just forward of the paddle box. A portion of the wave, and an immense mass of spray, dashed up on board the ship, and a quantity equal to several barrels of water came down upon the stairs where Hilbert was ascending. The poor fellow was almost strangled by the shock. He however clung manfully to the rope railing, and as soon as he recovered his breath he came back into the cabin.

Chapter IX.

The Passengers' Lottery

One morning, a few days after the storm described in the last chapter, Rollo was sitting upon one of the settees that stood around the skylight on the promenade deck, secured to their places by lashings of spun yarn, as has already been described, and was there listening to a conversation which was going on between two gentlemen that were seated on the next settee. The morning was very pleasant. The sun was shining, the air was soft and balmy, and the surface of the water was smooth. There was so little wind that the sails were all furled—for, in the case of a steamer at sea, the wind, even if it is fair, cannot help to impel the ship at all, unless it moves faster than the rate which the paddle wheels would of themselves carry her; and if it moves slower than this, of course, the steamer would by her own progress outstrip it, and the sails, if they were spread, would only be pressed back against the masts by the onward progress of the vessel, and thus her motion would only be retarded by them.

The steamer, on the day of which we are speaking, was going on very smoothly and rapidly by the power of her engines alone, and all the passengers were in excellent spirits. There was quite a company of them assembled at a place near one of the paddle boxes where smoking was allowed. Some were seated upon a settee that was placed there against the side of the paddle box, and others were standing around them. They were nearly all smoking, and, as they smoked, they were talking and laughing very merrily. Hilbert was among them, and he seemed to be listening very eagerly to what they were saying. Rollo was very strongly inclined to go out there, too, to hear what the men were talking about; but he was so much interested in what the gentlemen were saying who were near him, that he concluded to wait till they had finished their conversation, and then go.

The gentlemen who were near him were talking about the rockets—the same rockets that Rollo had seen when he went back to the stern of the ship to look out at the sea, on the day of the storm. One of the men, who had often been at sea before, and who seemed to be well acquainted with all nautical affairs, said that the rockets were used to throw lines from one ship to another, or from a ship to the shore, in case of wrecks or storms. He said that sometimes at sea a steamer came across a wrecked vessel, or one that was disabled, while yet there were some seamen or passengers still alive on board. These men would generally be seen clinging to the decks, or lashed to the rigging. In such cases the sea was often in so frightful a commotion that no boat could live in it; and there was consequently no way to get the unfortunate mariners off their vessel but by throwing a line across, and then drawing them over in some way or other along the line. He said that the sailors had a way of making a sort of sling, by which a man could be suspended under such a line with loops or rings, made of rope, and so adjusted that they would run along upon it; and that by this means men could be drawn across from one ship to another, at sea, if there was only a line stretched across for the rings to run upon.

Now, the rockets were used for the purpose of throwing such a line. A small light line was attached to the stick of the rocket, and then the rocket itself was fired, being pointed in such a manner as to go directly over the wrecked ship. If it was aimed correctly, it would fall down so as to carry the small line across the ship. Then the sailors on board the wrecked vessel would seize it, and by means of it would draw the end of a strong line over, and thus effect the means of making their escape. It was, however, a very dreadful alternative, after all; for the rope forming this fearful bridge would of course be subject all the time to the most violent jerkings, from the rolling and pitching of the vessels to which the two extremities of it were attached, and the unhappy men who had to be drawn over by means of it would be perhaps repeatedly struck and overwhelmed by the foaming surges on the way.

While Rollo was listening to this conversation, Hilbert's father and another gentleman who had been walking with him up and down the deck came and sat down on one of the settees. Very soon, Hilbert, seeing his father sitting there, came eagerly to him, and said, holding out his hand,—

"Father, I want you to give me half a sovereign."

"Half a sovereign!" repeated his father; "what do you want of half a sovereign?"

A sovereign is the common gold coin of England. The value of it is a pound, or nearly five dollars; and half a sovereign is, of course, in value about equal to two dollars and a half of American money.

"I want to get a ticket," said Hilbert. "Come, father, make haste," he added, with many impatient looks and gestures, and still holding out his hand.

"A ticket? what ticket?" asked his father. As he asked these questions, he put his hand in his pocket and drew out an elegant little purse.

"Why, they are going to have a lottery about the ship's run, to-day," replied Hilbert, "and I want a ticket. The tickets are half a sovereign apiece, and the one who gets the right one will have all the half sovereigns. There will be twenty of them, and that will make ten pounds."

"Nearly fifty dollars," said his father; "and what can you do with all that money, if you get it? O, no, Hibby; I can't let you have any money for that. And besides, these lotteries, and the betting about the run of the ship, are as bad as gambling. They are gambling, in fact."

"Why, father," said Hilbert, "you bet, very often."

Mr. Livingston, for that was his father's name, and his companion, the gentleman who was sitting with him, laughed at hearing this; and the gentleman said,—

"Ah, George, he has you there."

Even Hilbert looked pleased at the effect which his rejoinder had produced. In fact, he considered his half sovereign as already gained.

"O, let him have the half sovereign," continued the gentleman. "He'll find some way to spend the ten pounds, if he gets them, I'll guaranty."

So Mr. Livingston gave Hilbert the half sovereign, and he, receiving it with great delight, ran away.

The plan of the lottery, which the men at the paddle box were arranging, was this. In order, however, that the reader may understand it perfectly, it is necessary to make a little preliminary explanation in respect to the mode of keeping what is called the reckoning of ships and steamers at sea. When a vessel leaves the shore at New York, and loses sight of the Highlands of Neversink, which is the land that remains longest in view, the mariners that guide her have then more than two thousand miles to go, across a stormy and trackless ocean, with nothing whatever but the sun and stars, and their own calculations of their motion, to guide them. Now, unless at the end of the voyage they should come out precisely right at the lighthouse or at the harbor which they aim at, they might get into great difficulty or danger. They might run upon rocks where they expected a port, or come upon some strange and unknown land, and be entirely unable to determine which way to turn in order to find their destined haven.

The navigators could, however, manage this all very well, provided they could be sure of seeing the sun every day at proper times, particularly at noon. The sun passes through different portions of the sky every different day of the year, rising to a higher point at noon in the summer, and to a lower one in the winter. The place of the sun, too, in the sky, is different according as the observer is more to the northward or southward. For inasmuch as the sun, to the inhabitants of northern latitudes, always passes through the southern part of the sky, if one person stands at a place one hundred or five hundred miles to the southward of another, the sun will, of course, appear to be much higher over his head to the former than to the latter. The farther north, therefore, a ship is at sea, the lower in the sky, that is, the farther down toward the south, the sun will be at noon.

Navigators, then, at sea, always go out upon the deck at noon, if the sun is out, with a very curious and complicated instrument, called a sextant, in their hands; and with this instrument they measure exactly the distance from the sun at noon down to the southern horizon. This is called making an observation. When the observation is made, the captain takes the number of degrees and minutes, and goes into his state room; and there, by the help of certain tables contained in books which he always keeps there for the purpose, he makes a calculation, and finds out the exact latitude of the ship; that is, where she is, in respect to north and south. There are other observations and calculations by which he determines the longitude; that is, where the ship is in respect to east and west. When both these are determined, he can find the precise place on the chart where the vessel is, and so—inasmuch as he had ascertained by the same means where she was the day before—he can easily calculate how far she has come during the twenty-four hours between one noon and another. These calculations are always made at noon, because that is the time for making the observations on the sun. It takes about an hour to make the calculations. The passengers on board the ship during this interval are generally full of interest and curiosity to know the result. They come out from their lunch at half past twelve, and then they wait the remaining half hour with great impatience. They are eager to know how far they have advanced on their voyage since noon of the day before.

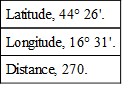

In order to let the passengers know the result, when it is determined, the captain puts up a written notice, thus:—

The passengers, on seeing this notice, which is called a bulletin, know at once, from the first two items, whereabouts on the ocean they are; and from the last they learn that the distance which the ship has come since the day before is 270 miles.

This plan of finding out the ship's place every day, and of ascertaining the distance which she has sailed since the day before, would be perfectly successful, and amply sufficient for all the purposes required, if the sun could always be seen when the hour arrived for making the observation; but this is not the fact. The sky is often obscured by clouds for many days in succession; and, in fact, it sometimes happens that the captain has scarcely an opportunity to get a good observation during the whole voyage. There is, therefore, another way by which the navigator can determine where the ship is, and how fast she gets along on her voyage.