Rollo on the Rhine

"Perhaps it could," said Rollo. "But every body that comes here to see it gets a great deal of pleasure; and as an immense number of people will come, I think the amount of the pleasure will be very great in all."

"That is true," said Mr. George, "and that is the right way to consider it; but let us make the calculation in the same way that we made the calculation about the gold chain that you were going to buy in London. If we suppose that the church was half done when they left off the work, and that it will now cost four millions of dollars to finish it, that will make eight millions of dollars in all. Now, what is the interest of eight millions of dollars, say at three per cent.?"

Rollo began to calculate it in his mind; but before he had got through, Mr. George said that it was two hundred and forty thousand dollars a year.

"That," said Mr. George, "is equal, with a proper allowance for repairs, to, say a thousand dollars per day. Now, do you think that the people who will come here to see it will get pleasure enough from it to amount in all to a thousand dollars a day?"

"I don't know," said Rollo, doubtfully. "I'd give one dollar, I know, to see it."

"Yes," said Mr. George, "so would I; and I do not know but that there would be three hundred thousand to come in a year, including all the great occasions that would bring out immense assemblages from all the surrounding country."

"At any rate, I hope they will finish it," said Rollo.

"So do I," said Mr. George.

"And I mean to put a little in the man's plate when I go down," said Rollo, "and then I shall have a share in it."

"I will too," said Mr. George.

Accordingly, as they passed by the man when they were leaving the church, Mr. George put a franc into his plate, and Rollo half a franc. Just at the time that they put their money in, the party that Minnie belonged to came by, and the gentleman put in a silver coin called a thaler, which is worth about seventy-five cents; so that Rollo had the satisfaction of seeing that one of the four millions of dollars was raised on the spot.

Chapter IV.

Travelling on the Rhine

The steamboats and hotels, and all the arrangements made for the accommodation of travellers on the Rhine, are entirely different from those of any American river, partly for the reason that so very large a portion of the travelling there is pleasure travelling. The boats are smaller, and they go more frequently. The company is more select. They sit upon the deck, under the awnings, all the day, looking at their guide books, and maps, and panoramas of the river, and studying out the names and history of the villages, and castles, and ruined towers, which they pass on the way. The hotels are large and very elegant. They are built on the banks of the river, or wherever there is the finest view, and the dining room is always placed in the best part of the house, the windows from it commanding views of the mountains, or overlooking the water, so that in sitting at table to eat your breakfast, or your dinner, you have before you all the time some charming view. Then there is usually connected with the dining room, and opening from it, some garden or terrace, raised above the road and the river, with seats and little tables there, shaded by trees, or sheltered by bowers, where ladies and gentlemen can sit, when the weather is pleasant, and read, or drink their tea or coffee, or explore, with an opera glass, or a spy glass, the scenery around. They can see the towers and castles across the river, and follow the little paths leading in zigzag lines up among the vineyards to the watchtowers, and pavilions, and belvideres, that are built on the pinnacles of the rocks, or on the summits of the lower mountains.

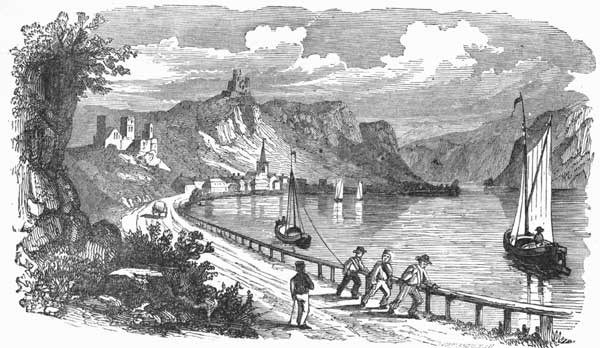

The hotels and inns, even in the smallest villages, are very nice and elegant in all their interior arrangements. These small villages consist usually of a crowded collection of the most quaint and queer-looking houses, or rather huts, of stone, with an antique and venerable-looking church in the midst of them, looking still more quaint and queer than the houses. The hotels, however, in these villages, or rather on the borders of them,—for the hotels are often built on the open ground beyond the town, where there is room for gardens and walks, and raised terraces around them,—are palaces in comparison with the dwellings of the inhabitants. And well they may be, for the villagers are almost all laborers of a very humble class—boatmen, who get their living by plying boats up and down the river; vinedressers, who cultivate the vineyards of the neighboring hills; or hostlers and coachmen, who take care of the carriages and of the horses employed in the traffic of the river. A great number of horses are employed; for not only are the carriages of such persons as choose to travel on the Rhine by land, or to make excursions on the banks of the river, drawn by them, but almost all the boats, except the steamboats that go up the river, are towed up by these animals. To enable them to do this, a regular tow path has been formed all the way up the river, on the left bank, and boats of all shapes and sizes are continually to be seen going up, drawn, like canal boats in America, by horses—and sometimes even by men. Once I saw some boys drawing up a small boat in this way. It seems they had been going down the stream to take a sail, or perhaps to convey a traveller down; and now they were coming up again, drawing their boat by walking along the bank, the current being so rapid that it is much easier to draw a boat up than it is to row it. The boys had a long line attached to the mast of their boat, and both of them were drawing upon this line by means of broad bands, forming a sort of harness, which were passed over their shoulders.

Now, the small villages that I was speaking of are formed almost exclusively of the dwellings of the various classes which I have described, while the hotels or inns that are built on the margins of them are intended, not as they would be in America, for the accommodation of the people of the same class, but for travellers of wealth, and rank, and distinction, who come from all quarters of the world to explore the beauties and study the antiquities of the Rhine. Thus the inns, however small and secluded they may be, and however retired and solitary the places in which they stand, are always very nice, and even elegant, in their interior arrangements. The chambers are furnished and arranged in the prettiest possible manner. Handsome open carriages and pretty boats are ready to convey visitors on any excursion which they may desire to make in the neighborhood, and the table is provided with almost as many delicacies and niceties as you can have in Paris.

The roads along the banks of the Rhine, too, are absolutely perfect. Well they may be so in fact, for workmen have been constantly employed in making and perfecting them for nearly two thousand years. Julius Cæsar worked upon them. Charlemagne worked upon them. Frederic the Great worked upon them. Napoleon worked upon them. They are walled up wherever necessary on the side towards the river; the rock is cut away on the side towards the land; valleys have been filled up; hill sides have been terraced, and ravines bridged over; until the road, though passing along the margin of a very mountainous region, is almost as level as a railway throughout the whole of its course. And as it is macadamized throughout, and is kept in the most perfect condition, it is always, in wet weather as well as dry, as firm, and hard, and smooth as a floor.

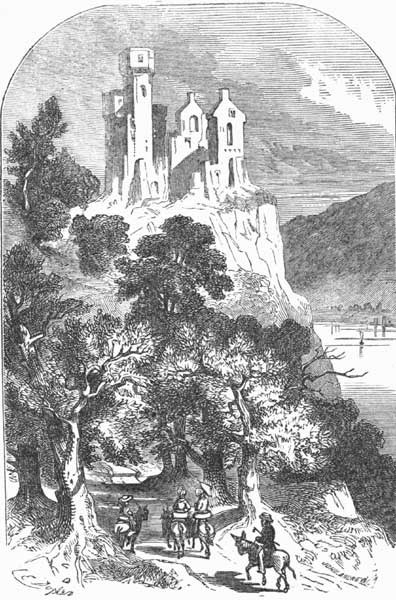

With such roads and such carriages on the land, and such pretty steamboats as they have upon the water, it would be very pleasant going up through the highlands of the Rhine, if there were nothing but the natural scenery to attract the eye of the traveller. But besides the quaint and ancient villages, and the curious old churches which adorn them,—villages which sometimes line the margin of the water, and sometimes cling to the slopes of the hills, or nestle in the higher valleys,—there are other still stronger attractions, in the castles, towers, and palaces, which are seen scattered every where on the river banks, adorning every prominent and commanding position along the shores, and crowning, in many cases, the summits of the hills. Many of these castles and towers, though built originally hundreds of years ago, are still kept in repair and inhabited, some being used as the summer residences of princes, or of private men of fortune, and others, being armed with cannon and garrisoned with soldiers, are held as strongholds by the kings, or dukes, or electors, in whose dominions they lie. There are a great many of them, however, that have been allowed to go to decay; and the ruins of these still stand, presenting to the eye of the traveller who gazes up to them from the deck of the steamer, or from his seat in his carriage, or who climbs up to visit them more closely, by means of the zigzag paths which lead to them, very interesting relics and memorials of ancient times. The ruins are generally on very lofty summits, and they usually occupy the most commanding positions, so that the view from them up and down the river is almost always very grand. The castles were built by the dukes, and barons, and other feudal chieftains of the middle ages, and they are placed in these commanding positions in order that the chieftains who lived in them might watch the river, and the roads leading along the banks of it, and come down with a troop of their followers to exact what they called tribute, but what those who had to pay it called plunder, from the merchants or travellers whom they saw from the windows of their watchtowers, passing up and down.

In fact these men were really robbers; being just like any other robbers, excepting that they restricted themselves to some rule and system in their plunderings, such as an enlightened regard for their own interest required. If, when they found a vessel laden with merchandise, or a company of travellers coming down the river, they had robbed them of every thing they possessed, the river and the roads would soon have been entirely abandoned, and their occupation would have been gone. In order to avoid this result, they were accustomed to content themselves with a certain portion of the value which the traveller was carrying; and they called the money which they exacted a tribute, or tax, paid for the privilege of passing through their dominions. They kept continual watch in their lofty castles, both up and down the river, to see who came by, and then, descending with a sufficient force to render resistance useless, they would take what they pretended to consider their due, and retreat with it to their almost inaccessible fastnesses, where they were safe from all pursuers.

They often had wars with one another; and in the progress of these wars the weaker chieftains became, in the course of time, subjected to the stronger, and thus two or more small dominions would often become united into one. These amalgamations went on continually; and as they advanced, the condition of the cultivator of the ground, and of the peaceful merchant or traveller, was improved, for the rules and regulations for the collection of the tribute became more fixed and settled, and men knew more and more what they could calculate upon, and could regulate their business accordingly. Arrangements were made, too, to collect a regular tax from the cultivators of the ground; and just so far as these arrangements were matured, and the produce of the plunder, or the tribute, or the tax, or whatever we call it, increased, just so far it became for the interest of the chieftains that the cultivation of the land and the traffic on the river should be increased, and should be protected from all depredations but their own. Thus a system of law grew up, and arrangements for preserving public order, for promoting the general industry, and rules and regulations for the collection of the tribute, until at length, when all these arrangements were matured, and the multitude of petty chieftains became combined under one great chieftain ruling over the whole, and collecting the revenue for his subordinates, we find a great kingdom as the result, in which the descendants of the ancient marauders that lived in castles on the hills, under the name of princes and nobles, collect the means of enabling themselves to live in idleness and luxury out of the avails of the labor of the agriculturists, the merchants, and the manufacturers, by a combined and concerted arrangement, and a regular system of rents, taxes, and tolls, instead of by irregular forrays and depredations, as in former years.

When any one of these nobles is questioned as to the nature of his claim to the enjoyment of so large a portion of the produce of the land, without doing any thing to earn or deserve it, he says that it is a vested right; that is, that he has a right to claim and take a certain portion of the proceeds of the toil of the present generation of laborers, because his forefathers claimed and took a similar portion from theirs. And the one monarch, whose ancestors succeeded in overpowering or crowding out the others, claims his right to rule on the same ground. Thus, in the progress of ages, by a strange commutation, robbery and plunder, when systematized, and extended, and established on a permanent basis, become legitimacy, and the divine right of kings.

In America there is no such division of the fruits of industry between those who do the work and a class of idle nobles, and soldiers, and priests, who do nothing but consume the proceeds of it. There every man possesses the full fruit of his labor, except so far as he himself joins with his fellow-citizens in setting apart a portion for the purposes of public and general utility. This is the reason why such immense numbers of laboring men are every year leaving Germany and emigrating to America.

But to return to the Rhine. Of course, just so fast and so far as the smaller chieftains were conquered and dispossessed, and the country came into the hands of a smaller number of greater princes, the old castles became useless. Besides, when rules and laws, instead of surprises and violence, became the means by which contributions were levied, it was no longer necessary to have strongholds on high hills to come down from, when a vessel or a traveller was coming by, and to retreat to with the booty when the plunder had been taken. A great number of these old castles have, therefore, gone to decay; for they were generally built too high on the hills and rocks to be convenient as dwellings for peaceable men. A few of the largest and strongest of them were retained as fortresses; and those that were retained have been greatly enlarged and strengthened in their defences in modern times, so that some of them are now the greatest and strongest fortresses in the world. Others, that were built in tolerably accessible situations, or which commanded an unusually beautiful view, were retained and kept in repair, and are used now as the summer residences of wealthy men. The rest were suffered gradually to go to decay, and the ruins and remains of them are seen crowning almost every remarkable height all along the river. Some of these ruins are still in a very good state of preservation, so that in going up to explore them you can make out very easily the whole original plan of the edifice. You can find the turret, with the remains of the stairs which led up to the watchtower, and the kitchen, and the hall, and the armory, and the stables. In others, there is nothing to be seen but a confused mass of unintelligible ruins; and in others still, every thing is gone, except, perhaps, some single arch or gateway, which stands among a mass of shapeless mounds, the last remaining relic of the edifice it once adorned, and itself tottering, perhaps, on the brink of its precipitous foundation, as if just ready to fall.

These old ruins are visited every year by thousands of persons who come from every part of the world to see them. These visitors arrive every year in such numbers that the steamboats, both going up and coming down, and all the hotels, and thousands of carriages, which are perpetually plying to and fro along the shores on both sides of the river, are constantly filled with them. A great many people merely pass up or down the river in a steamer, in a day and a night, and only see the ruins and the other scenery by gazing at them from the deck of the vessel. But in this case they get no idea whatever of the Rhine. It is necessary to travel slowly, to stop frequently at the towns on the bank, to make excursions along the shores and into the interior, and to ascend to the sites of the ruins, and to other elevated points, so as to view the valley and the stream meandering through it from above, or you obtain no correct idea whatever of travelling on the Rhine.

DONKEY RIDING.

The work of ascending to the old ruins would be a very arduous and difficult one for all but the young and robust, were it not for the assistance that is afforded by the donkeys that are kept at the foot of every remarkable hill that travellers might be supposed desirous to ascend. These donkeys have a sort of chair fitted upon them, that is, a saddle, flat upon the top, and guarded all around one side by a sort of back, like the back of a chair. The trappings are covered with some kind of scarlet cloth, so that the troop of donkeys standing together under the shade of the trees, at the foot of the hill which they are to ascend, make a very gay appearance. The donkeys look very small to bear so heavy a load as a full grown person; but they are very strong, and they carry their burden quite easily, especially as the distance is not very great. For these mountains of the Rhine, celebrated as they are for the romantic grandeur which they impart to the scenery, are, after all, seldom more than a few hundred feet high. There is also, almost always, an excellent path leading up to them. It winds usually by zigzags through the groves of trees, or between gardens and vineyards, in a very delightful manner, so that the ascent in going up any of these hills would make a very pleasant excursion even without the ruins on the top.

Such, in its general features, is the mountainous region of the Rhine, as it appears to the travellers who go to visit it at the present day; and it was this region that Rollo and Mr. George were now going to explore.

Chapter V.

The Sieben Gebirgen

The word Sieben means seven, and Gebirgen means mountains.6 Thus the Sieben Gebirgen is the Seven Mountains. It is the name given to a mountainous mass of land which rises into seven or more principal peaks, just at the entrance of the romantic part of the Rhine. The highest of these mountains is the celebrated Drachenfels, which has a ruined castle on the top of it, and an inn for the accommodation of travellers just below. The Seven Mountains and Drachenfels are on the east bank of the river. Opposite to them on the left bank are some other remarkable mountains, crowned also with celebrated ruins. The river flows between these highlands as through a gateway. They form, in fact, the commencement of the mountainous region of the Rhine, in ascending the river from Cologne.7

The large town next below where these mountains commence is Bonn, which is, perhaps, thirty or forty miles above Cologne. The country up as far as Bonn from Cologne is pretty level, and a railroad has been made there. At Bonn the mountains begin, and the railroad has accordingly not been yet carried any farther. Mr. George and Rollo went up to Bonn by the railroad.

Mr. George wished to stop at Bonn for half a day to visit a celebrated university that is there. The buildings of this university were formerly a palace; but they were afterwards given up to the use of the university, which subsequently became one of the most distinguished seminaries of learning in Europe. Mr. George wished to visit this university. He had letters of introduction to some of the professors. He wished also to see the library and the cabinets of natural history that were there. He invited Rollo to go with him, but Rollo concluded not to go. He would have liked to have seen the library very well, and the cabinets, but he was rather afraid of the professors.

So, while Mr. George went to visit the literary institution, Rollo amused himself by rambling about the town, and looking at the quaint old churches, and the houses, and the fortifications, and in strolling along the quay, by the shore of the river, to see the steamers and tow boats go up and down.

At length he went to the hotel. The hotel was just without the gates, near the river. There was a garden between the hotel and the river, with a terrace at the margin of it, overlooking the water, where there were tables and chairs ready for any person who might choose to take coffee or any other refreshments there. Mr. George's room was on this side of the hotel, and being pretty high it overlooked the gardens, and the terrace, and the river, and afforded a charming view. Up the river, on the other side, about three or four miles off, the Sieben Gebirgen were plainly to be seen, the summits of them tipped with ancient ruins.

After Rollo had been sitting there about half an hour, Mr. George came home. It was then about one o'clock.

"Well, Rollo," said he, "we are going up the river. I have engaged the landlord to send us up in a carriage to some pleasant place on the bank of the river among the mountains, where we can spend the Sabbath."

"Why, what day is it?" asked Rollo.

"It is Saturday," replied Mr. George.

Rollo was quite surprised to find that it was Saturday. In fact, in travelling on the Rhine, as there is so little to mark or distinguish one day from another, we almost always soon lose our reckoning.

"What is the name of the place where we are going?" asked Rollo.

"I don't know," replied Mr. George. "I cannot understand very well. He is going to send us somewhere. How it will turn out I cannot tell. We must trust to the fortune of war."

Mr. George often called the luck that befell him in travelling the fortune of war. "If we were contented," he would say, "to travel over and over again in places that we know, then we could make some calculations, and could know beforehand, in most cases, where we were going and how we should come out. But in travelling in new and strange places we cannot tell at all, especially when there is no language that we can communicate well with the people in. So we have to trust to the fortune of war."

Mr. George, however, determined to make one more effort to find out where he was going; and so, when the carriage came to the door, and he and Rollo were about to get into it, he asked the porter of the house—who was the man that "spoke English"—what the name of the place was where they were going to stop.

"Yes, sare," replied the man. "You will stop. You will go to Poppensdorf and to Kreitzberg, and then you will go to Gottesberg, and then you will go to Rolandseck, where there is a boat that will take you to Drachenfels, or to Kœnigswinter."

He said all this with so strong a German accent, and pronounced the barbarous words with so foreign an intonation, that no trace or impression whatever was left by them on Mr. George's ear.

"But which is the place," asked Mr. George, speaking very deliberately and plainly,—"which is the place where we are to be left by the carriage to stay on Sunday? Is it Rolandseck or Kœnigswinter?"

"Yes, sare," said the porter, making a very polite bow. "Yes, sare, you will go to Rolandseck, and to Kreitzberg, and to Gottesberg, and if you please you can stop at Poppensdorf."

"Very well," said Mr. George. "Tell him to drive on."

This is a tolerably fair specimen of the success to which travellers, and the porters, and waiters, who "speak English," attain to, in their attempts to understand one another. In fact, the attempts of these domestic linguists to speak English are sometimes still more unfortunate than their attempts to understand it. One of them, in talking to Mr. George, said "No, yes," for no, sir. Another told Rollo that the dinner would be ready in fiveteen minutes, and a very worthy landlord, in commenting on the pleasant weather, said that the time was very agregable. So a waiter said one day that the bifstek was just coming up out of the kriken. He meant kitchen.