Hannibal

Hannibal's intrigues with Antiochus.

Things being in this state, the enemies of Hannibal at Carthage sent information to the Roman senate that he was negotiating and plotting with Antiochus to combine the Syrian and Carthaginian forces against them, and thus plunge the world into another general war. The Romans accordingly determined to send an embassage to the Carthaginian government, and to demand that Hannibal should be deposed from his office, and given up to them a prisoner, in order that he might be tried on this charge.

Embassy from Rome.

These commissioners came, accordingly, to Carthage, keeping, however, the object of their mission a profound secret, since they knew very well that, if Hannibal should suspect it, he would make his escape before the Carthaginian senate could decide upon the question of surrendering him. Hannibal was, however, too wary for them. He contrived to learn their object, and immediately resolved on making his escape. He knew that his enemies in Carthage were numerous and powerful, and that the animosity against him was growing stronger and stronger. He did not dare, therefore, to trust to the result of the discussion in the senate, but determined to fly.

Flight of Hannibal.

He had a small castle or tower on the coast, about one hundred and fifty miles southeast of Carthage. He sent there by an express, ordering a vessel to be ready to take him to sea. He also made arrangements to have horsemen ready at one of the gates of the city at nightfall. During the day he appeared freely in the public streets, walking with an unconcerned air, as if his mind was at ease, and giving to the Roman embassadors, who were watching his movements, the impression that he was not meditating an escape. Toward the close of the day, however, after walking leisurely home, he immediately made preparations for his journey. As soon as it was dark he went to the gate of the city, mounted the horse which was provided for him, and fled across the country to his castle. Here he found the vessel ready which he had ordered. He embarked, and put to sea.

Island of Cercina.

There is a small island called Cercina at a little distance from the coast. Hannibal reached this island on the same day that he left his tower. There was a harbor here, where merchant ships were accustomed to come in. He found several Phœnician vessels in the port, some bound to Carthage. Hannibal's arrival produced a strong sensation here, and, to account for his appearance among them, he said he was going on an embassy from the Carthaginian government to Tyre.

Stratagem of Hannibal.

He sails for Syria.

He was now afraid that some of these vessels that were about setting sail for Carthage might carry the news back of his having being seen at Cercina, and, to prevent this, he contrived, with his characteristic cunning, the following plan. He sent around to all the ship-masters in the port, inviting them to a great entertainment which he was to give, and asked, at the same time, that they would lend him the main-sails of their ships, to make a great awning with, to shelter the guests from the dews of the night. The ship-masters, eager to witness and enjoy the convivial scene which Hannibal's proposal promised them, accepted the invitation, and ordered their main-sails to be taken down. Of course, this confined all their vessels to port. In the evening, the company assembled under the vast tent, made by the main-sails, on the shore. Hannibal met them, and remained with them for a time. In the course of the night, however, when they were all in the midst of their carousing, he stole away, embarked on board a ship, and set sail, and, before the ship-masters could awake from the deep and prolonged slumbers which followed their wine, and rig their main-sails to the masts again, Hannibal was far out of reach on his way to Syria.

Excitement at Carthage.

Hannibal safe at Ephesus.

In the mean time, there was a great excitement produced at Carthage by the news which spread every where over the city, the day after his departure, that he was not to be found. Great crowds assembled before his house. Wild and strange rumors circulated in explanation of his disappearance, but they were contradictory and impossible, and only added to the universal excitement. This excitement continued until the vessels at last arrived from Cercina, and made the truth known. Hannibal was himself, however, by this time, safe beyond the reach of all possible pursuit. He was sailing prosperously, so far as outward circumstances were concerned, but dejected and wretched in heart, toward Tyre. He landed there in safety, and was kindly received. In a few days he went into the interior, and, after various wanderings, reached Ephesus, where he found Antiochus, the Syrian king.

Carthaginian deputies.

The change of fortune.

As soon as the escape of Hannibal was made known at Carthage, the people of the city immediately began to fear that the Romans would consider them responsible for it, and that they should thus incur a renewal of Roman hostility. In order to avert this danger, they immediately sent a deputation to Rome, to make known the fact of Hannibal's flight, and to express the regret they felt on account of it, in hopes thus to save themselves from the displeasure of their formidable foes. It may at first view seem very ungenerous and ungrateful in the Carthaginians to abandon their general in this manner, in the hour of his misfortune and calamity, and to take part against him with enemies whose displeasure he had incurred only in their service and in executing their will. And this conduct of the Carthaginians would have to be considered as not only ungenerous, but extremely inconsistent, if it had been the same individuals that acted in the two cases. But it was not. The men and the influences which now opposed Hannibal's projects and plans had opposed them always and from the beginning; only, so long as he went on successfully and well, they were in the minority, and Hannibal's adherents and friends controlled all the public action of the city. But, now that the bitter fruits of his ambition and of his totally unjustifiable encroachments on the Roman territories and Roman rights began to be realized, the party of his friends was overturned, the power reverted to the hands of those who had always opposed him, and in trying to keep him down when he was once fallen, their action, whether politically right or wrong, was consistent with itself, and can not be considered as at all subjecting them to the charge of ingratitude or treachery.

Hannibal's unconquerable spirit.

His new plans.

One might have supposed that all Hannibal's hopes and expectations of ever again coping with his great Roman enemy would have been now effectually and finally destroyed, and that henceforth he would have given up his active hostility and would have contented himself with seeking some refuge where he could spend the remainder of his days in peace, satisfied with securing, after such dangers and escapes, his own personal protection from the vengeance of his enemies. But it is hard to quell and subdue such indomitable perseverance and energy as his. He was very little inclined yet to submit to his fate. As soon as he found himself at the court of Antiochus, he began to form new plans for making war against Rome. He proposed to the Syrian monarch to raise a naval force and put it under his charge. He said that if Antiochus would give him a hundred ships and ten or twelve thousand men, he would take the command of the expedition in person, and he did not doubt that he should be able to recover his lost ground, and once more humble his ancient and formidable enemy. He would go first, he said, with his force to Carthage, to get the co-operation and aid of his countrymen there in his new plans. Then he would make a descent upon Italy, and he had no doubt that he should soon regain the ascendency there which he had formerly held.

Hannibal sends a secret messenger to Carthage.

Hannibal's design of going first to Carthage with his Syrian army was doubtless induced by his desire to put down the party of his enemies there, and to restore the power to his adherents and partisans. In order to prepare the way the more effectually for this, he sent a secret messenger to Carthage, while his negotiations with Antiochus were going on, to make known to his friends there the new hopes which he began to cherish, and the new designs which he had formed. He knew that his enemies in Carthage would be watching very carefully for any such communication; he therefore wrote no letters, and committed nothing to paper which, on being discovered, might betray him. He explained, however, all his plans very fully to his messenger, and gave him minute and careful instructions as to his manner of communicating them.

The placards.

The Carthaginian authorities were indeed watching very vigilantly, and intelligence was brought to them, by their spies, of the arrival of this stranger. They immediately took measures for arresting him. The messenger, who was himself as vigilant as they, got intelligence of this in his secret lurking-place in the city, and determined immediately to fly. He, however, first prepared some papers and placards, which he posted up in public places, in which he proclaimed that Hannibal was far from considering himself finally conquered; that he was, on the contrary, forming new plans for putting down his enemies in Carthage, resuming his former ascendency there, and carrying fire and sword again into the Roman territories; and, in the mean time, he urged the friends of Hannibal in Carthage to remain faithful and true to his cause.

Excitement produced by them.

The messenger, after posting his placards, fled from the city in the night, and went back to Hannibal. Of course, the occurrence produced considerable excitement in the city. It aroused the anger and resentment of Hannibal's enemies, and awakened new encouragement and hope in the hearts of his friends. Further than this, however, it led to no immediate results. The power of the party which was opposed to Hannibal was too firmly established at Carthage to be very easily shaken. They sent information to Rome of the coming of Hannibal's emissary to Carthage, and of the result of his mission, and then every thing went on as before.

Roman commissioners.

Supposed interview of Hannibal and Scipio.

Hannibal's opinion of Alexander and Pyrrhus.

In the mean time, the Romans, when they learned where Hannibal had gone, sent two or three commissioners there to confer with the Syrian government in respect to their intentions and plans, and watch the movements of Hannibal. It was said that Scipio himself was joined to this embassy, and that he actually met Hannibal at Ephesus, and had several personal interviews and conversations with him there. Some ancient historian gives a particular account of one of these interviews, in which the conversation turned, as it naturally would do between two such distinguished commanders, on military greatness and glory. Scipio asked Hannibal whom he considered the greatest military hero that had ever lived. Hannibal gave the palm to Alexander the Great, because he had penetrated, with comparatively a very small number of Macedonian troops, into such remote regions, conquered such vast armies, and brought so boundless an empire under his sway. Scipio then asked him who he was inclined to place next to Alexander. He said Pyrrhus. Pyrrhus was a Grecian, who crossed the Adriatic Sea, and made war, with great success, against the Romans. Hannibal said that he gave the second rank to Pyrrhus because he systematized and perfected the art of war, and also because he had the power of awakening a feeling of personal attachment to himself on the part of all his soldiers, and even of the inhabitants of the countries that he conquered, beyond any other general that ever lived. Scipio then asked Hannibal who came next in order, and he replied that he should give the third rank to himself. "And if," added he, "I had conquered Scipio, I should consider myself as standing above Alexander, Pyrrhus, and all the generals that the world ever produced."

Anecdotes.

Various other anecdotes are related of Hannibal during the time of his first appearance in Syria, all indicating the very high degree of estimation in which he was held, and the curiosity and interest that were every where felt to see him. On one occasion, it happened that a vain and self-conceited orator, who knew little of war but from his own theoretic speculations, was haranguing an assembly where Hannibal was present, being greatly pleased with the opportunity of displaying his powers before so distinguished an auditor. When the discourse was finished, they asked Hannibal what he thought of it. "I have heard," said he, in reply, "many old dotards in the course of my life, but this is, verily, the greatest dotard of them all."

Hannibal's efforts prove vain.

Antiochus agrees to give him up.

Hannibal failed, notwithstanding all his perseverance, in obtaining the means to attack the Romans again. He was unwearied in his efforts, but, though the king sometimes encouraged his hopes, nothing was ever done. He remained in this part of the world for ten years, striving continually to accomplish his aims, but every year he found himself farther from the attainment of them than ever. The hour of his good fortune and of his prosperity were obviously gone. His plans all failed, his influence declined, his name and renown were fast passing away. At last, after long and fruitless contests with the Romans, Antiochus made a treaty of peace with them, and, among the articles of this treaty, was one agreeing to give up Hannibal into their power.

Hannibal's treasures.

Hannibal resolved to fly. The place of refuge which he chose was the island of Crete. He found that he could not long remain here. He had, however, brought with him a large amount of treasure, and when about leaving Crete again, he was uneasy about this treasure, as he had some reason to fear that the Cretans were intending to seize it. He must contrive, then, some stratagem to enable him to get this gold away. The plan he adopted was this:

His plan for securing them.

He filled a number of earthen jars with lead, covering the tops of them with gold and silver. These he carried, with great appearance of caution and solicitude, to the Temple of Diana, a very sacred edifice, and deposited them there, under very special guardianship of the Cretans, to whom, as he said, he intrusted all his treasures. They received their false deposit with many promises to keep it safely, and then Hannibal went away with his real gold cast in the center of hollow statues of brass, which he carried with him, without suspicion, as objects of art of very little value.

Hannibal's unhappy condition.

Hannibal fled from kingdom to kingdom, and from province to province, until life became a miserable burden. The determined hostility of the Roman senate followed him every where, harassing him with continual anxiety and fear, and destroying all hope of comfort and peace. His mind was a prey to bitter recollections of the past, and still more dreadful forebodings for the future. He had spent all the morning of his life in inflicting the most terrible injuries on the objects of his implacable animosity and hate, although they had never injured him, and now, in the evening of his days, it became his destiny to feel the pressure of the same terror and suffering inflicted upon him. The hostility which he had to fear was equally merciless with that which he had exercised; perhaps it was made still more intense by being mingled with what they who felt it probably considered a just resentment and revenge.

The potion of poison.

Hannibal fails in his attempt to escape.

He poisons himself.

When at length Hannibal found that the Romans were hemming him in more and more closely, and that the danger increased of his falling at last into their power, he had a potion of poison prepared, and kept it always in readiness, determined to die by his own hand rather than to submit to be given up to his enemies. The time for taking the poison at last arrived. The wretched fugitive was then in Bithynia, a kingdom of Asia Minor. The King of Bithynia sheltered him for a time, but at length agreed to give him up to the Romans. Hannibal learning this, prepared for flight. But he found, on attempting his escape, that all the modes of exit from the palace which he occupied, even the secret ones which he had expressly contrived to aid his flight, were taken possession of and guarded. Escape was, therefore, no longer possible, and Hannibal went to his apartment and sent for the poison. He was now an old man, nearly seventy years of age, and he was worn down and exhausted by his protracted anxieties and sufferings. He was glad to die. He drank the poison, and in a few hours ceased to breathe.

Chapter XII.

The Destruction of Carthage

B.C. 146-145Destruction.

The third Punic war.

The consequences of Hannibal's reckless ambition, and of his wholly unjustifiable aggression on Roman rights to gratify it, did not end with his own personal ruin. The flame which he had kindled continued to burn until at last it accomplished the entire and irretrievable destruction of Carthage. This was effected in a third and final war between the Carthaginians and the Romans, which is known in history as the third Punic war. With a narrative of the events of this war, ending, as it did, in the total destruction of the city, we shall close this history of Hannibal.

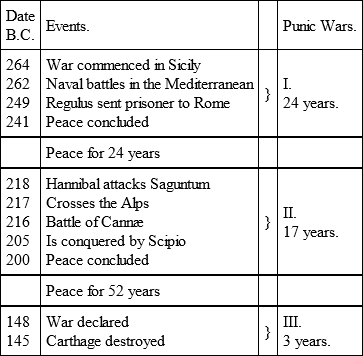

Chronological table of the Punic wars.

It will be recollected that the war which Hannibal himself waged against Rome was the second in the series, the contest in which Regulus figured so prominently having been the first. The one whose history is now to be given is the third. The reader will distinctly understand the chronological relations of these contests by the following table:

TABLE.

Character of the Punic wars.

Intervals between them.

These three Punic wars extended, as the table shows, over a period of more than a hundred years. Each successive contest in the series was shorter, but more violent and desperate than its predecessor, while the intervals of peace were longer. Thus the first Punic war continued for twenty-four years, the second about seventeen, and the third only three or four. The interval, too, between the first and second was twenty-four years, while between the second and third there was a sort of peace for about fifty years. These differences were caused, indeed, in some degree, by the accidental circumstances on which the successive ruptures depended, but they were not entirely owing to that cause. The longer these belligerent relations between the two countries continued, and the more they both experienced the awful effects and consequences of their quarrels, the less disposed they were to renew such dreadful struggles, and yet, when they did renew them they engaged in them with redoubled energy of determination and fresh intensity of hate. Thus the wars followed each other at greater intervals, but the conflicts, when they came, though shorter in duration, were more and more desperate and merciless in character.

Animosities and dissensions.

We have said that, after the close of the second Punic war, there was a sort of peace for about fifty years. Of course, during this time, one generation after another of public men arose, both in Rome and Carthage, each successive group, on both sides, inheriting the suppressed animosity and hatred which had been cherished by their predecessors. Of course, as long as Hannibal had lived, and had continued his plots and schemes in Syria, he was the means of keeping up a continual irritation among the people of Rome against the Carthaginian name. It is true that the government at Carthage disavowed his acts, and professed to be wholly opposed to his designs; but then it was, of course, very well known at Rome that this was only because they thought he was not able to execute them. They had no confidence whatever in Carthaginian faith or honesty, and, of course, there could be no real harmony or stable peace.

Numidia.

Numidian horsemen.

There arose gradually, also, another source of dissension. By referring to the map, the reader will perceive that there lies, to the westward of Carthage, a country called Numidia. This country was a hundred miles or more in breadth, and extended back several hundred miles into the interior. It was a very rich and fertile region, and contained many powerful and wealthy cities. The inhabitants were warlike, too, and were particularly celebrated for their cavalry. The ancient historians say that they used to ride their horses into the field without saddles, and often without bridles, guiding and controlling them by their voices, and keeping their seats securely by the exercise of great personal strength and consummate skill. These Numidian horsemen are often alluded to in the narratives of Hannibal's campaigns, and, in fact, in all the military histories of the times.

Masinissa.

Among the kings who reigned in Numidia was one who had taken sides with the Romans in the second Punic war. His name was Masinissa. He became involved in some struggle for power with a neighboring monarch named Syphax, and while he, that is, Masinissa, had allied himself to the Romans, Syphax had joined the Carthaginians, each chieftain hoping, by this means, to gain assistance from his allies in conquering the other. Masinissa's patrons proved to be the strongest, and at the end of the second Punic war, when the conditions of peace were made, Masinissa's dominions were enlarged, and the undisturbed possession of them confirmed to him, the Carthaginians being bound by express stipulations not to molest him in any way.

Parties at Rome and Carthage.

Their differences.

In commonwealths like those of Rome and Carthage, there will always be two great parties struggling against each other for the possession of power. Each wishes to avail itself of every opportunity to oppose and thwart the other, and they consequently almost always take different sides in all the great questions of public policy that arise. There were two such parties at Rome, and they disagreed in respect to the course which should be pursued in regard to Carthage, one being generally in favor of peace, the other perpetually calling for war. In the same manner there was at Carthage a similar dissension, the one side in the contest being desirous to propitiate the Romans and avoid collisions with them, while the other party were very restless and uneasy under the pressure of the Roman power upon them, and were endeavoring continually to foment feelings of hostility against their ancient enemies, as if they wished that war should break out again. The latter party were not strong enough to bring the Carthaginian state into an open rupture with Rome itself, but they succeeded at last in getting their government involved in a dispute with Masinissa, and in leading out an army to give him battle.

Masinissa prepares for war.

Fifty years had passed away, as has already been remarked, since the close of Hannibal's war. During this time, Scipio – that is, the Scipio who conquered Hannibal – had disappeared from the stage. Masinissa himself was very far advanced in life, being over eighty years of age. He, however, still retained the strength and energy which had characterized him in his prime. He drew together an immense army, and mounting, like his soldiers, bare-back upon his horse, he rode from rank to rank, gave the necessary commands, and matured the arrangements for battle.

Hasdrubal.

Carthage declares war.

The name of the Carthaginian general on this occasion was Hasdrubal. This was a very common name at Carthage, especially among the friends and family of Hannibal. The bearer of it, in this case, may possibly have received it from his parents in commemoration of the brother of Hannibal, who lost his head in descending into Italy from the Alps, inasmuch as during the fifty years of peace which had elapsed, there was ample time for a child born after that event to grow up to full maturity. At any rate, the new Hasdrubal inherited the inveterate hatred to Rome which characterized his namesake, and he and his party had contrived to gain a temporary ascendency in Carthage, and they availed themselves of their brief possession of power to renew, indirectly at least, the contest with Rome. They sent the rival leaders into banishment, raised an army, and Hasdrubal himself taking the command of it, they went forth in great force to encounter Masinissa.