Hannibal

Plan of Nero.

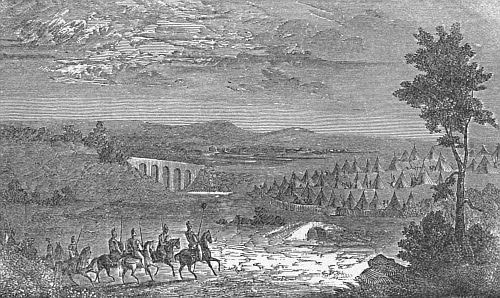

Nero, after much anxious deliberation, concluded that the emergency in which he found himself placed was one requiring him to take the responsibility of disobedience. He did not, however, dare to go northward with all his forces, for that would be to leave southern Italy wholly at the mercy of Hannibal. He selected, therefore, from his whole force, which consisted of forty thousand men, seven or eight thousand of the most efficient and trustworthy; the men on whom he could most securely rely, both in respect to their ability to bear the fatigues of a rapid march, and the courage and energy with which they would meet Hasdrubal's forces in battle at the end of it. He was, at the time when Hasdrubal's letters were intercepted, occupying a spacious and well-situated camp. This he enlarged and strengthened, so that Hannibal might not suspect that he intended any diminution of the forces within. All this was done very promptly, so that, in a few hours after he received the intelligence on which he was acting, he was drawing off secretly, at night, a column of six or eight thousand men, none of whom knew at all where they were going.

A night march.

He proceeded as rapidly as possible to the northward, and, when he arrived in the northern province, he contrived to get into the camp of Livius as secretly as he had got out from his own. Thus, of the two armies, the one where an accession of force was required was greatly strengthened at the expense of the other, without either of the Carthaginian generals having suspected the change.

Livius and Nero attack Hasdrubal.

Livius was rejoiced to get so opportune a re-enforcement. He recommended that the troops should all remain quietly in camp for a short time, until the newly-arrived troops could rest and recruit themselves a little after their rapid and fatiguing march; but Nero opposed this plan, and recommended an immediate battle. He knew the character of the men that he had brought, and he was, besides, unwilling to risk the dangers which might arise in his own camp, in southern Italy, by too long an absence from it. It was decided, accordingly, to attack Hasdrubal at once, and the signal for battle was given.

Hasdrubal orders a retreat.

Butchery of Hasdrubal's army.

Hasdrubal's death.

It is not improbable that Hasdrubal would have been beaten by Livius alone, but the additional force which Nero had brought made the Romans altogether too strong for him. Besides, from his position in the front of the battle, he perceived, from some indications that his watchful eye observed, that a part of the troops attacking him were from the southward; and he inferred from this that Hannibal had been defeated, and that, in consequence of this, the whole united force of the Roman army was arrayed against him. He was disheartened and discouraged, and soon ordered a retreat. He was pursued by the various divisions of the Roman army, and the retreating columns of the Carthaginians were soon thrown into complete confusion. They became entangled among rivers and lakes; and the guides who had undertaken to conduct the army, finding that all was lost, abandoned them and fled, anxious only to save their own lives. The Carthaginians were soon pent up in a position where they could not defend themselves, and from which they could not escape. The Romans showed them no mercy, but went on killing their wretched and despairing victims until the whole army was almost totally destroyed. They cut off Hasdrubal's head, and Nero sat out the very night after the battle to return with it in triumph to his own encampment. When he arrived, he sent a troop of horse to throw the head over into Hannibal's camp, a ghastly and horrid trophy of his victory.

Hannibal was overwhelmed with disappointment and sorrow at the loss of his army, bringing with it, as it did, the destruction of all his hopes. "My fate is sealed," said he; "all is lost. I shall send no more news of victory to Carthage. In losing Hasdrubal my last hope is gone."

Hasdrubal's Head.

Progress of the Roman arms.

Successes of Scipio.

While Hannibal was in this condition in Italy, the Roman armies, aided by their allies, were gaining gradually against the Carthaginians in various parts of the world, under the different generals who had been placed in command by the Roman senate. The news of these victories came continually home to Italy, and encouraged and animated the Romans, while Hannibal and his army, as well as the people who were in alliance with him, were disheartened and depressed by them. Scipio was one of these generals commanding in foreign lands. His province was Spain. The news which came home from his army became more and more exciting, as he advanced from conquest to conquest, until it seemed that the whole country was going to be reduced to subjection. He overcame one Carthaginian general after another until he reached New Carthage, which he besieged and conquered, and the Roman authority was established fully over the whole land.

Scipio then returned in triumph to Rome. The people received him with acclamations. At the next election they chose him consul. On the allotment of provinces, Sicily fell to him, with power to cross into Africa if he pleased. It devolved on the other consul to carry on the war in Italy more directly against Hannibal. Scipio levied his army, equipped his fleet, and sailed for Sicily.

Scipio in Africa.

The first thing that he did on his arrival in his province was to project an expedition into Africa itself. He could not, as he wished, face Hannibal directly, by marching his troops into the south of Italy, for this was the work allotted to his colleague. He could, however, make an incursion into Africa, and even threaten Carthage itself, and this, with the boldness and ardor which marked his character, he resolved to do.

Carthage threatened.

He was triumphantly successful in all his plans. His army, imbibing the spirit of enthusiasm which animated their commander, and confident of success, went on, as his forces in Spain had done, from victory to victory. They conquered cities, they overran provinces, they defeated and drove back all the armies which the Carthaginians could bring against them, and finally they awakened in the streets and dwellings of Carthage the same panic and consternation which Hannibal's victorious progress had produced in Rome.

A truce.

The Carthaginians being now, in their turn, reduced to despair, sent embassadors to Scipio to beg for peace, and to ask on what terms he would grant it and withdraw from the country. Scipio replied that he could not make peace. It rested with the Roman senate, whose servant he was. He specified, however, certain terms which he was willing to have proposed to the senate, and, if the Carthaginians would agree to them, he would grant them a truce, that is, a temporary suspension of hostilities, until the answer of the Roman senate could be returned.

Hannibal recalled.

The Carthaginians agreed to the terms. They were very onerous. The Romans say that they did not really mean to abide by them, but acceded for the moment in order to gain time to send for Hannibal. They had great confidence in his resources and military power, and thought that, if he were in Africa, he could save them. At the same time, therefore, that they sent their embassadors to Rome with their propositions for peace, they dispatched expresses to Hannibal, ordering him to embark his troops as soon as possible, and, abandoning Italy, to hasten home, to save, if it was not already too late, his native city from destruction.

When Hannibal received these messages, he was overwhelmed with disappointment and sorrow. He spent hours in extreme agitation, sometimes in a moody silence, interrupted now and then by groans of despair, and sometimes uttering loud and angry curses, prompted by the exasperation of his feelings. He, however, could not resist. He made the best of his way to Carthage. The Roman senate, at the same time, instead of deciding on the question of peace or war, which Scipio had submitted to them, referred the question back to him. They sent commissioners to Scipio, authorizing him to act for them, and to decide himself alone whether the war should be continued or closed, and if to be closed, on what conditions.

Hannibal raises a new army.

The Romans capture his spies.

Hannibal raised a large force at Carthage, joining with it such remains of former armies as had been left after Scipio's battles, and he went forth at the head of these troops to meet his enemy. He marched five days, going, perhaps, seventy-five or one hundred miles from Carthage, when he found himself approaching Scipio's camp. He sent out spies to reconnoiter. The patrols of Scipio's army seized these spies and brought them to the general's tent, as they supposed, for execution. Instead of punishing them, Scipio ordered them to be led around his camp, and to be allowed to see every thing they desired. He then dismissed them, that they might return to Hannibal with the information they had obtained.

Interview between Hannibal and Scipio.

Of course, the report which they brought in respect to the strength and resources of Scipio's army was very formidable to Hannibal. He thought it best to make an attempt to negotiate a peace rather than to risk a battle, and he accordingly sent word to Scipio requesting a personal interview. Scipio acceded to this request, and a place was appointed for the meeting between the two encampments. To this spot the two generals repaired at the proper time, with great pomp and parade, and with many attendants. They were the two greatest generals of the age in which they lived, having been engaged for fifteen or twenty years in performing, at the head of vast armies, exploits which had filled the world with their fame. Their fields of action had, however, been widely distant, and they met personally now for the first time. When introduced into each other's presence, they stood for some time in silence, gazing upon and examining one another with intense interest and curiosity, but not speaking a word.

Negotiations.

At length, however, the negotiation was opened. Hannibal made Scipio proposals for peace. They were very favorable to the Romans, but Scipio was not satisfied with them. He demanded still greater sacrifices than Hannibal was willing to make. The result, after a long and fruitless negotiation, was, that each general returned to his camp and prepared for battle.

The last battle.

Defeat of the Carthaginians.

In military campaigns, it is generally easy for those who have been conquering to go on to conquer: so much depends upon the expectations with which the contending armies go into battle. Scipio and his troops expected to conquer. The Carthaginians expected to be beaten. The result corresponded. At the close of the day on which the battle was fought, forty thousand Carthaginians were dead and dying upon the ground, as many more were prisoners in the Roman camp, and the rest, in broken masses, were flying from the field in confusion and terror, on all the roads which led to Carthage. Hannibal arrived at the city with the rest, went to the senate, announced his defeat, and said that he could do no more. "The fortune which once attended me," said he, "is lost forever, and nothing is left to us but to make peace with our enemies on any terms that they may think fit to impose."

Chapter XI.

Hannibal a Fugitive and an Exile

B.C. 200-182Hannibal's conquests.

Hannibal's life was like an April day. Its brightest glory was in the morning. The setting of his sun was darkened by clouds and showers. Although for fifteen years the Roman people could find no general capable of maintaining the field against him, Scipio conquered him at last, and all his brilliant conquests ended, as Hanno had predicted, only in placing his country in a far worse condition than before.

Peaceful pursuits.

The danger of a spirit of ambition and conquest.

In fact, as long as the Carthaginians confined their energies to useful industry, and to the pursuits of commerce and peace, they were prosperous, and they increased in wealth, and influence, and honor every year. Their ships went every where, and were every where welcome. All the shores of the Mediterranean were visited by their merchants, and the comforts and the happiness of many nations and tribes were promoted by the very means which they took to swell their own riches and fame. All might have gone on so for centuries longer, had not military heroes arisen with appetites for a more piquant sort of glory. Hannibal's father was one of the foremost of these. He began by conquests in Spain and encroachments on the Roman jurisdiction. He inculcated the same feelings of ambition and hate in Hannibal's mind which burned in his own. For many years, the policy which they led their countrymen to pursue was successful. From being useful and welcome visitors to all the world, they became the masters and the curse of a part of it. So long as Hannibal remained superior to any Roman general that could be brought against him, he went on conquering. But at last Scipio arose, greater than Hannibal. The tide was then turned, and all the vast conquests of half a century were wrested away by the same violence, bloodshed, and misery with which they had been acquired.

Gradual progress of Scipio's victories.

We have described the exploits of Hannibal, in making these conquests, in detail, while those of Scipio, in wresting them away, have been passed over very briefly, as this is intended as a history of Hannibal, and not of Scipio. Still Scipio's conquests were made by slow degrees, and they consumed a long period of time. He was but about eighteen years of age at the battle of Cannæ, soon after which his campaigns began, and he was thirty when he was made consul, just before his going into Africa. He was thus fifteen or eighteen years in taking down the vast superstructure of power which Hannibal had raised, working in regions away from Hannibal and Carthage during all this time, as if leaving the great general and the great city for the last. He was, however, so successful in what he did, that when, at length, he advanced to the attack of Carthage, every thing else was gone. The Carthaginian power had become a mere hollow shell, empty and vain, which required only one great final blow to effect its absolute demolition. In fact, so far spent and gone were all the Carthaginian resources, that the great city had to summon the great general to its aid the moment it was threatened, and Scipio destroyed them both together.

Severe conditions of peace exacted by Scipio.

And yet Scipio did not proceed so far as literally and actually to destroy them. He spared Hannibal's life, and he allowed the city to stand; but the terms and conditions of peace which he exacted were such as to put an absolute and perpetual end to Carthaginian dominion. By these conditions, the Carthaginian state was allowed to continue free and independent, and even to retain the government of such territories in Africa as they possessed before the war; but all their foreign possessions were taken away; and even in respect to Africa, their jurisdiction was limited and curtailed by very hard restrictions. Their whole navy was to be given to the Romans except ten small ships of three banks of oars, which Scipio thought the government would need for the purposes of civil administration. These they were allowed to retain. Scipio did not say what he should do with the remainder of the fleet: it was to be unconditionally surrendered to him. Their elephants of war were also to be all given up, and they were to be bound not to train any more. They were not to appear at all as a military power in any other quarter of the world but Africa, and they were not to make war in Africa except by previously making known the occasion for it to the Roman people, and obtaining their permission. They were also to pay to the Romans a very large annual tribute for fifty years.

Debates in the Carthaginian senate.

There was great distress and perplexity in the Carthaginian councils while they were debating these cruel terms. Hannibal was in favor of accepting them. Others opposed. They thought it would be better still to continue the struggle, hopeless as it was, than to submit to terms so ignominious and fatal.

Hannibal was present at these debates, but he found himself now in a very different position from that which he had been occupying for thirty years as a victorious general at the head of his army. He had been accustomed there to control and direct every thing. In his councils of war, no one spoke but at his invitation, and no opinion was expressed but such as he was willing to hear. In the Carthaginian senate, however, he found the case very different. There, opinions were freely expressed, as in a debate among equals, Hannibal taking his place among the rest, and counting only as one. And yet the spirit of authority and command which he had been so long accustomed to exercise, lingered still, and made him very impatient and uneasy under contradiction. In fact, as one of the speakers in the senate was rising to animadvert upon and oppose Hannibal's views, he undertook to pull him down and silence him by force. This proceeding awakened immediately such expressions of dissatisfaction and displeasure in the assembly as to show him very clearly that the time for such domineering was gone. He had, however, the good sense to express the regret he soon felt at having so far forgotten the duties of his new position, and to make an ample apology.

The Burning of the Carthaginian Fleet.

Terms of peace complied with.

Surrender of the elephants and ships.

The Carthaginians decided at length to accede to Scipio's terms of peace. The first instalment of the tribute was paid. The elephants and the ships were surrendered. After a few days, Scipio announced his determination not to take the ships away with him, but to destroy them there. Perhaps this was because he thought the ships would be of little value to the Romans, on account of the difficulty of manning them. Ships, of course, are useless without seamen, and many nations in modern times, who could easily build a navy, are debarred from doing it, because their population does not furnish sailors in sufficient numbers to man and navigate it. It was probably, in part, on this account that Scipio decided not to take the Carthaginian ships away, and perhaps he also wanted to show to Carthage and to the world that his object in taking possession of the national property of his foes was not to enrich his own country by plunder, but only to deprive ambitious soldiers of the power to compromise any longer the peace and happiness of mankind by expeditions for conquest and power. However this may be, Scipio determined to destroy the Carthaginian fleet, and not to convey it away.

Scipio burns the Carthaginian fleet.

Feelings of the spectators.

On a given day, therefore, he ordered all the galleys to be got together in the bay opposite to the city of Carthage, and to be burned. There were five hundred of them, so that they constituted a large fleet, and covered a large expanse of the water. A vast concourse of people assembled upon the shores to witness the grand conflagration. The emotion which such a spectacle was of itself calculated to excite was greatly heightened by the deep but stifled feelings of resentment and hate which agitated every Carthaginian breast. The Romans, too, as they gazed upon the scene from their encampment on the shore, were agitated as well, though with different emotions. Their faces beamed with an expression of exultation and triumph as they saw the vast masses of flame and columns of smoke ascending from the sea, proclaiming the total and irretrievable ruin of Carthaginian pride and power.

Scipio sails to Rome.

His reception.

Having thus fully accomplished his work, Scipio set sail for Rome. All Italy had been filled with the fame of his exploits in thus destroying the ascendency of Hannibal. The city of Rome had now nothing more to fear from its great enemy. He was shut up, disarmed, and helpless, in his own native state, and the terror which his presence in Italy had inspired had passed forever away. The whole population of Rome, remembering the awful scenes of consternation and terror which the city had so often endured, regarded Scipio as a great deliverer. They were eager to receive and welcome him on his arrival. When the time came and he approached the city, vast throngs went out to meet him. The authorities formed civic processions to welcome him. They brought crowns, and garlands, and flowers, and hailed his approach with loud and prolonged acclamations of triumph and joy. They gave him the name of Africanus, in honor of his victories. This was a new honor – giving to a conqueror the name of the country that he had subdued; it was invented specially as Scipio's reward, the deliverer who had saved the empire from the greatest and most terrible danger by which it had ever been assailed.

Hannibal's position and standing at Carthage.

Hannibal, though fallen, retained still in Carthage some portion of his former power. The glory of his past exploits still invested his character with a sort of halo, which made him an object of general regard, and he still had great and powerful friends. He was elevated to high office, and exerted himself to regulate and improve the internal affairs of the state. In these efforts he was not, however, very successful. The historians say that the objects which he aimed to accomplish were good, and that the measures for effecting them were, in themselves, judicious; but, accustomed as he was to the authoritative and arbitrary action of a military commander in camp, he found it hard to practice that caution and forbearance, and that deference for the opinion of others, which are so essential as means of influencing men in the management of the civil affairs of a commonwealth. He made a great many enemies, who did every thing in their power, by plots and intrigues, as well as by open hostility, to accomplish his ruin.

Orders from Rome.

Hannibal's mortification.

His pride, too, was extremely mortified and humbled by an occurrence which took place very soon after Scipio's return to Rome. There was some occasion of war with a neighboring African tribe, and Hannibal headed some forces which were raised in the city for the purpose, and went out to prosecute it. The Romans, who took care to have agents in Carthage to keep them acquainted with all that occurred, heard of this, and sent word to Carthage to warn the Carthaginians that this was contrary to the treaty, and could not be allowed. The government, not willing to incur the risk of another visit from Scipio, sent orders to Hannibal to abandon the war and return to the city. Hannibal was compelled to submit; but after having been accustomed, as he had been, for many years, to bid defiance to all the armies and fleets which Roman power could, with their utmost exertion, bring against him, it must have been very hard for such a spirit as his to find itself stopped and conquered now by a word. All the force they could command against him, even at the very gates of their own city, was once impotent and vain. Now, a mere message and threat, coming across the distant sea, seeks him out in the remote deserts of Africa, and in a moment deprives him of all his power.

Years passed away, and Hannibal, though compelled outwardly to submit to his fate, was restless and ill at ease. His scheming spirit, spurred on now by the double stimulus of resentment and ambition, was always busy, vainly endeavoring to discover some plan by which he might again renew the struggle with his ancient foe.

Syria and Phœnicia.

King Antiochus.

It will be recollected that Carthage was originally a commercial colony from Tyre, a city on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea. The countries of Syria and Phœnicia were in the vicinity of Tyre. They were powerful commercial communities, and they had always retained very friendly relations with the Carthaginian commonwealth. Ships passed continually to and fro, and always, in case of calamities or disasters threatening one of these regions, the inhabitants naturally looked to the other for refuge and protection, Carthage looking upon Phœnicia as its mother, and Phœnicia regarding Carthage as her child. Now there was, at this time, a very powerful monarch on the throne in Syria and Phœnicia, named Antiochus. His capital was Damascus. He was wealthy and powerful, and was involved in some difficulties with the Romans. Their conquests, gradually extending eastward, had approached the confines of Antiochus's realms, and the two nations were on the brink of war.