William the Conqueror

Scouts sent out.

William's supper.

While these operations were going on, William dispatched small squadrons of horse as reconnoitering parties, to explore the country around, to see if there were any indications that Harold was near. These parties returned, one after another, after having gone some miles into the country in all directions, and reported that there were no signs of an enemy to be seen. Things were now getting settled, too, in the camp, and William gave directions that the army should kindle their camp fires for the night, and prepare and eat their suppers. His own supper, or dinner, as perhaps it might be called, was also served, which he partook, with his officers, in his own tent. His mind was in a state of great contentment and satisfaction at the successful accomplishment of the landing, and at finding himself thus safely established, at the head of a vast force, within the realm of England.

The missing ships.

Every circumstance of the transit had been favorable excepting one, and that was, that two of the ships belonging to the fleet were missing. William inquired at supper if any tidings of them had been received. They told him, in reply, that the missing vessels had been heard from; they had, in some way or other, been run upon the rocks and lost. There was a certain astrologer, who had made a great parade, before the expedition left Normandy, of predicting its result. He had found, by consulting the stars, that William would be successful, and would meet with no opposition from Harold. This astrologer had been on board one of the missing ships, and was drowned. William remarked, on receiving this information, "What an idiot a man must be, to think that he can predict, by means of the stars, the future fate of others, when it is so plain that he can not foresee his own!"

The Conqueror's Stone.

It is said that William's dinner on this occasion was served on a large stone instead of a table. The stone still remains on the spot, and is called "the Conqueror's Stone" to this day.

March of the army.

Flight of the inhabitants.

The next day after the landing, the army was put in motion, and advanced along the coast toward the eastward. There was no armed enemy to contend against them there or to oppose their march; the people of the country, through which the army moved, far from attempting to resist them, were filled with terror and dismay. This terror was heightened, in fact, by some excesses of which some parties of the soldiers were guilty. The inhabitants of the hamlets and villages, overwhelmed with consternation at the sudden descent upon their shores of such a vast horde of wild and desperate foreigners, fled in all directions. Some made their escape into the interior; others, taking with them the helpless members of their households, and such valuables as they could carry, sought refuge in monasteries and churches, supposing that such sanctuaries as those, not even soldiers, unless they were pagans, would dare to violate. Others, still, attempted to conceal themselves in thickets and fens till the vast throng which was sweeping onward like a tornado should have passed. Though William afterward always evinced a decided disposition to protect the peaceful inhabitants of the country from all aggressions on the part of his troops, he had no time to attend to that subject now. He was intent on pressing forward to a place of safety.

The army encamps.

The town of Hastings.

William's fortifications.

Approach of Harold.

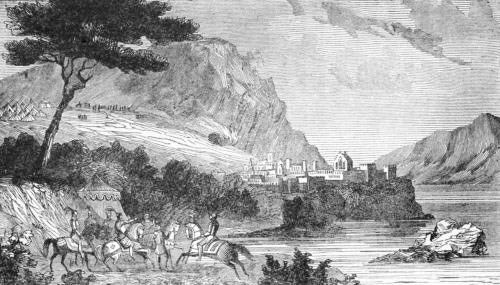

William reached at length a position which seemed to him suitable for a permanent encampment. It was an elevated land, near the sea. To the westward of it was a valley formed by a sort of recess opened in the range of chalky cliffs which here form the shore of England. In the bottom of this valley, down upon the beach, was a small town, then of no great consequence or power, but whose name, which was Hastings, has since been immortalized by the battle which was fought in its vicinity a few days after William's arrival. The position which William selected for his encampment was on high land in the vicinity of the town. The lines of the encampment were marked out, and the forts or castles which had been brought from Normandy were set up within the inclosures. Vast multitudes of laborers were soon at work, throwing up embankments, and building redoubts and bastions, while others were transporting the arms, the provisions, and the munitions of war, and storing them in security within the lines. The encampment was soon completed, and the long line of tents were set up in streets and squares within it. By the time, however, that the work was done, some of William's agents and spies came into camp from the north, saying that in four days Harold would be upon him at the head of a hundred thousand men.

Chapter X.

The Battle of Hastings

A.D. 1066Tostig.

He is driven from England.

The reader will doubtless recollect that the tidings which William first received of the accession of King Harold were brought to him by Tostig, Harold's brother, on the day when he was trying his bow and arrows in the park at Rouen. Tostig was his brother's most inveterate foe. He had been, during the reign of Edward, a great chieftain, ruling over the north of England. The city of York was then his capital. He had been expelled from these his dominions, and had quarreled with his brother Harold in respect to his right to be restored to them. In the course of this quarrel he was driven from the country altogether, and went to the Continent, burning with rage and resentment against his brother; and when he came to inform William of Harold's usurpation, his object was not merely to arouse William to action—he wished to act himself. He told William that he himself had more influence in England still than his brother, and that if William would supply him with a small fleet and a moderate number of men, he would make a descent upon the coast and show what he could do.

Expedition of Tostig.

William acceded to his proposal, and furnished him with the force which he required, and Tostig set sail. William had not, apparently, much confidence in the power of Tostig to produce any great effect, but his efforts, he thought, might cause some alarm in England, and occasion sudden and fatiguing marches to the troops, and thus distract and weaken King Harold's forces. William would not, therefore, accompany Tostig himself, but, dismissing him with such force as he could readily raise on so sudden a call, he remained himself in Normandy, and commenced in earnest his own grand preparations, as is described in the last chapter.

He sails to Norway.

Tostig's alliance with the Norwegians.

Tostig did not think it prudent to attempt a landing on English shores until he had obtained some accession to the force which William had given him. He accordingly passed through the Straits of Dover, and then turning northward, he sailed along the eastern shores of the German Ocean in search of allies. He came, at length, to Norway. He entered into negotiations there with the Norwegian king, whose name, too, was Harold. This northern Harold was a wild and adventurous soldier and sailor, a sort of sea king, who had spent a considerable portion of his life in marauding excursions upon the seas. He readily entered into Tostig's views. An arrangement was soon concluded, and Tostig set sail again to cross the German Ocean toward the British shores, while Harold promised to collect and equip his own fleet as soon as possible, and follow him. All this took place early in September; so that, at the same time that William's threatened invasion was gathering strength and menacing Harold's southern frontier, a cloud equally dark and gloomy, and quite as threatening in its aspect, was rising and swelling in the north; while King Harold himself, though full of vague uneasiness and alarm, could gain no certain information in respect to either of these dangers.

The Norwegian fleet.

Superstitions.

Dreams of the soldiers.

The Norwegian fleet assembled at the port appointed for the rendezvous of it, but, as the season was advanced and the weather stormy, the soldiers there, like William's soldiers on the coast of France, were afraid to put to sea. Some of them had dreams which they considered as bad omens; and so much superstitious importance was attached to such ideas in those times that these dreams were gravely recorded by the writers of the ancient chronicles, and have come down to us as part of the regular and sober history of the times. One soldier dreamed that the expedition had sailed and landed on the English coast, and that there the English army came out to meet them. Before the front of the army rode a woman of gigantic stature, mounted on a wolf. The wolf had in his jaws a human body, dripping with blood, which he was engaged in devouring as he came along. The woman gave the wolf another victim after he had devoured the first.

Another of these ominous dreams was the following: Just as the fleet was about setting sail, the dreamer saw a crowd of ravenous vultures and birds of prey come and alight every where upon the sails and rigging of the ships, as if they were going to accompany the expedition. Upon the summit of a rock near the shore there sat the figure of a female, with a stern and ferocious countenance, and a drawn sword in her hand. She was busy counting the ships, pointing at them, as she counted, with her sword. She seemed a sort of fiend of destruction, and she called out to the birds, to encourage them to go. "Go!" said she, "without fear; you shall have abundance of prey. I am going too."

The combined fleets.

It is obvious that these dreams might as easily have been interpreted to portend death and destruction to their English foes as to the dreamers themselves. The soldiers were, however, inclined—in the state of mind which the season of the year, the threatening aspect of the skies, and the certain dangers of their distant expedition, produced—to apply the gloomy predictions which they imagined these dreams expressed, to themselves. Their chief, however, was of too desperate and determined a character to pay any regard to such influences. He set sail. His armament crossed the German Sea in safety, and joined Tostig on the coast of Scotland. The combined fleet moved slowly southward, along the shore, watching for an opportunity to land.

The Norwegians at Scarborough.

Attack on Scarborough.

The rolling fire.

They reached, at length, the town of Scarborough, and landed to attack it. The inhabitants retired within the walls, shut the gates, and bid the invaders defiance. The town was situated under a hill, which rose in a steep acclivity upon one side. The story is, that the Norwegians went upon this hill, where they piled up an enormous heap of trunks and branches of trees, with the interstices filled with stubble, dried bark, and roots, and other such combustibles, and then setting the whole mass on fire, they rolled it down into the town—a vast ball of fire, roaring and crackling more and more, by the fanning of its flames in the wind, as it bounded along. The intelligent reader will, of course, pause and hesitate, in considering how far to credit such a story. It is obviously impossible that any mere pile, however closely packed, could be made to roll. But it is, perhaps, not absolutely impossible that trunks of trees might be framed together, or fastened with wet thongs or iron chains, after being made in the form of a rude cylinder or ball, and filled with combustibles within, so as to retain its integrity in such a descent.

Burning of Scarborough.

The account states that this strange method of bombardment was successful. The town was set on fire; the people surrendered. Tostig and the Norwegians plundered it, and then, embarking again in their ships, they continued their voyage.

The intelligence of this descent upon his northern coasts reached Harold in London toward the close of September, just as he was withdrawing his forces from the southern frontier, as was related in the last chapter, under the idea that the Norman invasion would probably be postponed until the spring; so that, instead of sending his troops into their winter quarters, he had to concentrate them again with all dispatch, and march at the head of them to the north, to avert this new and unexpected danger.

Tostig marches to York.

Surrender of the city.

While King Harold was thus advancing to meet them, Tostig and his Norwegian allies entered the River Humber. Their object was to reach the city of York, which had been Tostig's former capital, and which was situated near the River Ouse, a branch of the Humber. They accordingly ascended the Humber to the mouth of the Ouse, and thence up the latter river to a suitable point of debarkation not far from York. Here they landed and formed a great encampment. From this encampment they advanced to the siege of the city. The inhabitants made some resistance at first; but, finding that their cause was hopeless, they offered to surrender, and a treaty of surrender was finally concluded. This negotiation was closed toward the evening of the day, and Tostig and his confederate forces were to be admitted on the morrow. They therefore, feeling that their prize was secure, withdrew to their encampment for the night, and left the city to its repose.

Arrival of King Harold.

It so happened that King Harold arrived that very night, coming to the rescue of the city. He expected to have found an army of besiegers around the walls, but, instead of that, there was nothing to intercept his progress up to the very gates of the city. The inhabitants opened the gates to receive him, and the whole detachment which was marching under his command passed in, while Tostig and his Norwegian allies were sleeping quietly in their camp, wholly unconscious of the great change which had thus taken place in the situation of their affairs.

Movements of Tostig.

Surprise of Tostig and his allies.

Preparations for battle.

The next morning Tostig drew out a large portion of the army, and formed them in array, for the purpose of advancing to take possession of the city. Although it was September, and the weather had been cold and stormy, it happened that, on that morning, the sun came out bright, and the air was calm, giving promise of a warm day; and as the movement into the city was to be a peaceful one—a procession, as it were, and not a hostile march—the men were ordered to leave their coats of mail and all their heavy armor in camp, that they might march the more unencumbered. While they were advancing in this unconcerned and almost defenseless condition, they saw before them, on the road leading to the city, a great cloud of dust arising. It was a strong body of King Harold's troops coming out to attack them. At first, Tostig and the Norwegians were completely lost and bewildered at the appearance of so unexpected a spectacle. Very soon they could see weapons glittering here and there, and banners flying. A cry of "The enemy! the enemy!" arose, and passed along their ranks, producing universal alarm. Tostig and the Norwegian Harold halted their men, and marshaled them hastily in battle array. The English Harold did the same, when he had drawn up near to the front of the enemy; both parties then paused, and stood surveying one another. Presently there was seen advancing from the English side a squadron of twenty horsemen, splendidly armed, and bearing a flag of truce. They approached to within a short distance of the Norwegian lines, when a herald, who was among them, called out aloud for Tostig. Tostig came forward in answer to the summons. The herald then proclaimed to Tostig that his brother did not wish to contend with him, but desired, on the contrary, that they should live together in harmony. He offered him peace, therefore, if he would lay down his arms, and he promised to restore him his former possessions and honors.

Negotiations between Tostig and his brother.

Tostig seemed very much inclined to receive this proposition favorably. He paused and hesitated. At length he asked the messenger what terms King Harold would make with his friend and ally, the Norwegian Harold. "He shall have," replied the messenger, "seven feet of English ground for a grave. He shall have a little more than that, for he is taller than common men." "Then," replied Tostig, "tell my brother to prepare for battle. It shall never be said that I abandoned and betrayed my ally and friend."

The battle.

Death of Tostig.

The Norwegians retire.

The troop returned with Tostig's answer to Harold's lines, and the battle almost immediately began. Of course the most eager and inveterate hostility of the English army would be directed against the Norwegians and their king, whom they considered as foreign intruders, without any excuse or pretext for their aggression. It accordingly happened that, very soon after the commencement of the conflict, Harold the Norwegian fell, mortally wounded by an arrow in his throat. The English king then made new proposals to Tostig to cease the combat, and come to some terms of accommodation. But, in the mean time, Tostig had become himself incensed, and would listen to no overtures of peace. He continued the combat until he was himself killed. The remaining combatants in his army had now no longer any motive for resistance. Harold offered them a free passage to their ships, that they might return home in peace, if they would lay down their arms. They accepted the offer, retired on board their ships, and set sail. Harold then, having, in the mean time, heard of William's landing on the southern coast, set out on his return to the southward, to meet the more formidable enemy that menaced him there.

Harold attempts to surprise William.

His failure.

His army, though victorious, was weakened by the fatigues of the march, and by the losses suffered in the battle. Harold himself had been wounded, though not so severely as to prevent his continuing to exercise the command. He pressed on toward the south with great energy, sending messages on every side, into the surrounding country, on his line of march, calling upon the chieftains to arm themselves and their followers, and to come on with all possible dispatch, and join him. He hoped to advance so rapidly to the southern coast as to surprise William before he should have fully intrenched himself in his camp, and without his being aware of his enemy's approach. But William, in order to guard effectually against surprise, had sent out small reconnoitering parties of horsemen on all the roads leading northward, that they might bring him in intelligence of the first approach of the enemy. Harold's advanced guard met these parties, and saw them as they drove rapidly back to the camp to give the alarm. Thus the hope of surprising William was disappointed. Harold found, too, by his spies, as he drew near, to his utter dismay, that William's forces were four times as numerous as his own. It would, of course, be madness for him to think of attacking an enemy in his intrenchments with such an inferior force. The only alternative left him was either to retreat, or else to take some strong position and fortify himself there, in the hope of being able to resist the invaders and arrest their advance, though he was not strong enough to attack them.

Advice of Harold's counselors.

Some of his counselors advised him not to hazard a battle at all, but to fall back toward London, carrying with him or destroying every thing which could afford sustenance to William's army from the whole breadth of the land. This would soon, they said, reduce William's army to great distress for want of food, since it would be impossible for him to transport supplies across the Channel for so vast a multitude. Besides, they said, this plan would compel William, in the extremity to which he would be reduced, to make so many predatory excursions among the more distant villages and towns, as would exasperate the inhabitants, and induce them to join Harold's army in great numbers to repel the invasion. Harold listened to these counsels, but said, after consideration, that he could never adopt such a plan. He could not be so derelict to his duty as to lay waste a country which he was under obligations to protect and save, or compel his people to come to his aid by exposing them, designedly, to the excesses and cruelties of so ferocious an enemy.

He rejects it.

Harold's encampment.

The country alarmed.

Harold determined, therefore, on giving William battle. It was not necessary, however, for him to attack the invader. He perceived at once that if he should take a strong position and fortify himself in it, William must necessarily attack him, since a foreign army, just landed in the country, could not long remain inactive on the shore. Harold accordingly chose a position six or seven miles from William's camp, and fortified himself strongly there. Of course neither army was in sight of the other, or knew the numbers, disposition, or plans of the enemy. The country between them was, so far as the inhabitants were concerned, a scene of consternation and terror. No one knew at what point the two vast clouds of danger and destruction which were hovering near them would meet, or over what regions the terrible storm which was to burst forth when the hour of that meeting should come, would sweep in its destructive fury. The inhabitants, therefore, were every where flying in dismay, conveying away the aged and the helpless by any means which came most readily to hand; taking with them, too, such treasures as they could carry, and hiding, in rude and uncertain places of concealment, those which they were compelled to leave behind. The region, thus, which lay between the two encampments was rapidly becoming a solitude and a desolation, across which no communication was made, and no tidings passed to give the armies at the encampments intelligence of each other.

Harold's brothers.

Harold had two brothers among the officers of his army, Gurth and Leofwin. Their conduct toward the king seems to have been of a more fraternal character than that of Tostig, who had acted the part of a rebel and an enemy. Gurth and Leofwin, on the contrary, adhered to his cause, and, as the hour of danger and the great crisis which was to decide their fate drew nigh, they kept close to his side, and evinced a truly fraternal solicitude for his safety. It was they, specially, who had recommended to Harold to fall back on London, and not risk his life, and the fate of his kingdom, on the uncertain event of a battle.

He proposes to visit William's camp.

Harold's arrival at William's lines.

He reconnoiters the camp.

As soon as Harold had completed his encampment, he expressed a desire to Gurth to ride across the intermediate country and take a view of William's lines. Such an undertaking was less dangerous then than it would be at the present day; for now, such a reconnoitering party would be discovered from the enemy's encampment, at a great distance, by means of spy-glasses, and a twenty-four-pound shot or a shell would be sent from a battery to blow the party to pieces or drive them away. The only danger then was of being pursued by a detachment of horsemen from the camp, or surrounded by an ambuscade. To guard against these dangers, Harold and Gurth took the most powerful and fleetest horses in the camp, and they called out a small but strong guard of well-selected men to escort them. Thus provided and attended, they rode over to the enemy's lines, and advanced so near that, from a small eminence to which they ascended, they could survey the whole scene of William's encampment: the palisades and embankments with which it was guarded, which extended for miles; the long lines of tents within; the vast multitude of soldiers; the knights and officers riding to and fro, glittering with steel; and the grand pavilion of the duke himself, with the consecrated banner of the cross floating above it. Harold was very much impressed with the grandeur of the spectacle.

Harold's despondency.

After gazing on this scene for some time in silence, Harold said to Gurth that perhaps, after all, the policy of falling back would have been the wisest for them to adopt, rather than to risk a battle with so overwhelming a force as they saw before them. He did not know, he added, but that it would be best for them to change their plan, and adopt that policy now. Gurth said that it was too late. They had taken their stand, and now for them to break up their encampment and retire would be considered a retreat and not a maneuver, and it would discourage and dishearten the whole realm.