Aircraft and Submarines

It is not within the province of this book to go in detail into the diplomatic history of the submarine controversy between Germany and the United States. Suffice it to say, therefore, that from the very beginning the controversy held many possibilities of the disastrous ending which finally came to pass when diplomatic relations were broken off between the two countries on February 3, 1917, and a state of war was declared by President Wilson's proclamation of April 6, 1917.

The period between Germany's first War Zone Declaration and the President's proclamation – two months and three days more than two years – was crowded with incidents in which submarines and submarine warfare held the centre of the stage. It would be impossible within the compass of this story to give a complete survey of all the boats that were sunk and of all the lives that were lost. Nor would it be possible to recount all the deeds of heroism which this new warfare occasioned. Belligerents and neutrals alike were affected. American ships suffered, perhaps, to a lesser degree, than those of other neutrals, partly because of the determined stand taken by the United States Government. On May 1, 1915, the first American steamer, the Gulflight, was sunk. Six days later the world was shocked by the news that the Lusitania, one of the biggest British passenger liners, had been torpedoed without warning on May 7, 1915 and had been sunk with a loss of 1198 lives, of whom 124 were American citizens. Before this nation was goaded into war, more than 200 Americans were slain.

Notes were again exchanged between the two Governments. Though the German government at that time showed an inclination to abandon its position in the submarine controversy under certain conditions, sinkings of passenger and freight steamers without warning continued. All attempts on the part of the United States Government to come to an equitable understanding with Germany failed on account of the latter's refusal to give up submarine warfare, or at least those features of it which, though considered illegal and inhuman by the United States, seemed to be considered most essential by Germany.

Then came the German note of January 31, 1917, stating that "from February 1, 1917, sea traffic will be stopped with every available weapon and without further notice" in certain minutely described "prohibited zones around Great Britain, France, Italy, and in the Eastern Mediterranean."

The total tonnage sunk by German submarines from the beginning of the war up to February 1, 1917, has been given by British sources as over three million tons, while German authorities claimed four million. The result of the German edict for unrestricted submarine warfare has been rather appalling, even if it fell far short of German prophesies and hopes. During the first two weeks of February a total of ninety-seven ships with a tonnage of about 210,000 tons were sent to the bottom of the sea. Since then the German submarines have taken an even heavier toll. It has, however, become next to impossible, due to the restrictions of censorship, to compute any accurate figures for later totals, though it has become known from time to time that the Allied as well as the neutral losses have been very much higher during the five months of February to July, 1917 than during any other five months.

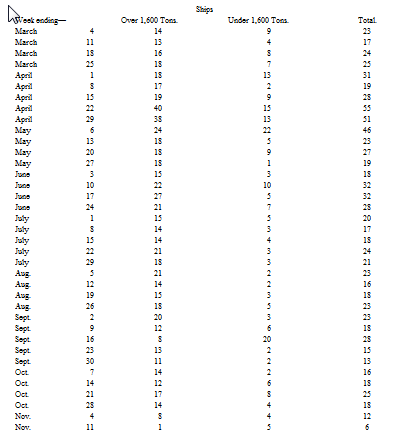

The figures of the losses of British merchantmen alone are shown by the following table:

The table with its week by week report of the British losses is of importance because at the time it was taken as a barometer indicative of German success or failure. The German admiralty at the moment of declaring the ruthless submarine war promised the people of Germany that they would sink a million tons a month and by so doing would force England to abject surrender in the face of starvation within three months. During that period the whole civilized world looked eagerly for the weekly statement of British losses. Only at one time was the German estimate of a million tons monthly obtained. Most of the time the execution done by the undersea boats amounted to less than half that figure. So far from England being beaten in three months, at the end of ten she was still unshattered, though sorely disturbed by the loss of so much shipping. Her new crops had come on and her statesmen declared that so far as the food supply was concerned they were safe for another year.

During this period of submarine activity the United States entered upon the war and its government immediately turned its attention to meeting the submarine menace. In the first four months literally nothing was accomplished toward this end. A few submarines were reported sunk by merchantmen, but in nearly every instance it was doubtful whether they were actually destroyed or merely submerged purposely in the face of a hostile fire. Americans were looked upon universally as a people of extraordinary inventive genius, and everywhere it was believed that by some sudden lucky thought an American would emerge from a laboratory equipped with a sovereign remedy for the submarine evil. Prominent inventors indeed declared their purpose of undertaking this search and went into retirement to study the problem. From that seclusion none had emerged with a solution at the end of ten months. When the submarine campaign was at its very height no one was able to suggest a better remedy for it than the building of cargo ships in such quantities that, sink as many as they might, the Germans would have to let enough slip through to sufficiently supply England with food and with the necessary munitions of war.

Many cruel sufferings befell seafaring people during the period of German ruthlessness on the high seas. An open boat, overcrowded with refugees, hastily provisioned as the ship to which it belonged was careening to its fate, and tossing on the open sea two or three hundred miles from shore in the icy nights of midwinter was no place of safety or of comfort. Yet the Germans so construed it, holding that when they gave passengers and crew of a ship time to take to the boats, they had fully complied with the international law providing that in the event of sinking a ship its people must first be given an opportunity to assure their safety.

There have been many harrowing stories of the experiences of survivors thus turned adrift. Under the auspices of the British government, Rudyard Kipling wrote a book detailing the agonies which the practice inflicted upon helpless human beings, including many women and children. Some of the survivors have told in graphic story the record of their actual experiences. Among these one of the most vivid is from the pen of a well-known American journalist, Floyd P. Gibbons, correspondent of the Chicago Tribune. He was saved from the British liner, Laconia, sunk by a German submarine, and thus tells the tale of his sufferings and final rescue:

I have serious doubts whether this is a real story. I am not entirely certain that it is not all a dream and that in a few minutes I will wake up back in stateroom B. 19 on the promenade deck of the Cunarder Laconia and hear my cockney steward informing me with an abundance of "and sirs" that it is a fine morning.

I am writing this within thirty minutes after stepping on the dock here in Queenstown from the British mine sweeper which picked up our open lifeboat after an eventful six hours of drifting, and darkness and baling and pulling on the oars and of straining aching eyes toward that empty, meaningless horizon in search of help. But, dream or fact, here it is:

The first-cabin passengers were gathered in the lounge Sunday evening, with the exception of the bridge fiends in the smoking-room. Poor Butterfly was dying wearily on the talking-machine and several couples were dancing.

About the tables in the smoke-room the conversation was limited to the announcement of bids and orders to the stewards. This group had about exhausted available discussion when the ship gave a sudden lurch sideways and forward. There was a muffled noise like the slamming of some large door at a good distance away. The slightness of the shock and the mildness of the report compared with my imagination was disappointing. Every man in the room was on his feet in an instant.

I looked at my watch. It was 10.30.

Then came five blasts on the whistle. We rushed down the corridor leading from the smoking-room at the stern to the lounge, which was amidships. We were running, but there was no panic. The occupants of the lounge were just leaving by the forward doors as we entered.

It was dark when we reached the lower deck. I rushed into my stateroom, grabbed life preservers and overcoat and made my way to the upper deck on that same dark landing.

I saw the chief steward opening an electric switch box in the wall and turning on the switch. Instantly the boat decks were illuminated. That illumination saved lives.

The torpedo had hit us well astern on the starboard side and had missed the engines and the dynamos. I had not noticed the deck lights before. Throughout the voyage our decks had remained dark at night and all cabin portholes were clamped down and all windows covered with opaque paint.

The illumination of the upper deck, on which I stood, made the darkness of the water, sixty feet below, appear all the blacker when I peered over the edge at my station boat, No. 10.

Already the boat was loading up and men and boys were busy with the ropes. I started to help near a davit that seemed to be giving trouble, but was stoutly ordered to get out of the way and get into the boat. We were on the port side, practically opposite the engine well. Up and down the deck passengers and crew were donning lifebelts, throwing on overcoats, and taking positions in the boats. There were a number of women, but only one appeared hysterical…

The boat started downward with a jerk toward the seemingly hungry rising and falling swells. Then we stopped and remained suspended in mid-air while the men at the bow and the stern swore and tusselled with the lowering ropes. The stern of the boat was down, the bow up, leaving us at an angle of about forty-five degrees. We clung to the seats to save ourselves from falling out.

"Who's got a knife? A knife! a knife!" bawled a sweating seaman in the bow.

"Great God! Give him a knife," bawled a half-dressed, gibbering negro stoker who wrung his hands in the stern.

A hatchet was thrust into my hand, and I forwarded it to the bow. There was a flash of sparks as it crashed down on the holding pulley. Many feet and hands pushed the boat from the side of the ship and we sagged down again, this time smacking squarely on the billowy top of a rising swell.

As we pulled away from the side of the ship its receding terrace of lights stretched upward. The ship was slowly turning over. We were opposite that part occupied by the engine rooms. There was a tangle of oars, spars and rigging on the seat and considerable confusion before four of the big sweeps could be manned on either side of the boat.

The gibbering bullet-headed negro was pulling directly behind me and I turned to quiet him as his frantic reaches with his oar were hitting me in the back.

"Get away from her, get away from her," he kept repeating. "When the water hits her hot boilers she'll blow up, and there's just tons and tons of shrapnel in the hold."

His excitement spread to other members of the crew in the boat.

It was the give-way of nerve tension. It was bedlam and nightmare.

We rested on our oars, with all eyes on the still lighted Laconia. The torpedo had struck at 10.30 P. M. It was thirty minutes afterward that another dull thud, which was accompanied by a noticeable drop in the hulk, told its story of the second torpedo that the submarine had despatched through the engine room and the boat's vitals from a distance of two hundred yards.

We watched silently during the next minute, as the tiers of lights dimmed slowly from white to yellow, then a red, and nothing was left but the murky mourning of the night, which hung over all like a pall.

A mean, cheese-coloured crescent of a moon revealed one horn above a ragged bundle of clouds low in the distance. A rim of blackness settled around our little world, relieved only by general leering stars in the zenith, and where the Laconia's lights had shone there remained only the dim outlines of a blacker hulk standing out above the water like a jagged headland, silhouetted against the overcast sky.

The ship sank rapidly at the stern until at last its nose stood straight in the air. Then it slid silently down and out of sight like a piece of disappearing scenery in a panorama spectacle.

Boat No. 3 stood closest to the ship and rocked about in a perilous sea of clashing spars and wreckage. As our boat's crew steadied its head into the wind a black hulk, glistening wet and standing about eight feet above the surface of the water, approached slowly and came to a stop opposite the boat and not six feet from the side of it.

"What ship was dot?" The correct words in throaty English with a German accent came from the dark hulk, according to Chief Steward Ballyn's statement to me later.

"The Laconia," Ballyn answered.

"Vot?"

"The Laconia, Cunard Line," responded the steward.

"Vot did she weigh?" was the next question from the submarine.

"Eighteen thousand tons."

"Any passengers?"

"Seventy-three," replied Ballyn, "men, women, and children, some of them in this boat. She had over two hundred in the crew."

"Did she carry cargo?"

"Yes."

"Well, you'll be all right. The patrol will pick you up soon." And without further sound save for the almost silent fixing of the conning tower lid, the submarine moved off.

There was no assurance of an early pick-up, even tho the promise were from a German source, for the rest of the boats, whose occupants – if they felt and spoke like those in my boat – were more than mildly anxious about their plight and the prospects of rescue.

The fear of some of the boats crashing together produced a general inclination toward further separation on the part of all the little units of survivors, with the result that soon the small craft stretched out for several miles, all of them endeavouring to keep their heads in the wind.

And then we saw the first light – the first sign of help coming – the first searching glow of white brilliance, deep down on the sombre sides of the black pot of night that hung over us.

It was way over there – first a trembling quiver of silver against the blackness; then, drawing closer, it defined itself as a beckoning finger, altho still too far away yet to see our feeble efforts to attract it…

We pulled, pulled, lustily forgetting the strain and pain of innards torn and racked from pain, vomiting – oblivious of blistered hands and wet, half frozen feet.

Then a nodding of that finger of light – a happy, snapping, crap-shooting finger that seemed to say: "Come on, you men," like a dice-player wooing the bones – led us to believe that our lights had been seen. This was the fact, for immediately the coming vessel flashed on its green and red side-lights and we saw it was headed for our position.

"Come alongside port!" was megaphoned to us. And as fast as we could we swung under the stern, while a dozen flashlights blinked down to us and orders began to flow fast and thick.

A score of hands reached out, and we were suspended in the husky tattooed arms of those doughty British jack tars, looking up into the weather-beaten, youthful faces, mumbling thanks and thankfulness and reading in the gold lettering on their pancake hats the legend "H. M. S. Laburnum."

Of course, the submarine fleets of the various navies paid a heavy toll too. It has become, however, increasingly difficult to get any accurate figures of these losses. The British navy, it is known, has lost during 1914, 1915, and 1916 twelve boats, some of which foundered, were wrecked or mined while others simply never returned. The loss of eight German submarines has also been definitely established. Others, however, are known to have been lost, and their number has been greatly increased since the arming of merchantmen. In 1917 it was estimated that the Germans lost one U-boat a week and built three.

Just what sensations a man experiences in a submerged submarine that finds it impossible to rise again, is, of course, more or less of a mystery. For, though submarines, the entire crew of which perished, have been raised later, only one record has ever been known to have been made covering the period during which death by suffocation or drowning stared their occupants in the face. This heroic and pathetic record was written in form of a letter by the commander of a Japanese submarine, Lieutenant Takuma Faotomu, whose boat, with its entire crew, was lost on April 15, 1910, during manœuvres in Hiroshima Bay. The letter reads in part as follows:

Although there is, indeed, no excuse to make for the sinking of his Imperial Majesty's boat and for the doing away of subordinates through my heedlessness, all on the boat have discharged their duties well and in everything acted calmly until death. Although we are departing in pursuance of our duty to the State, the only regret we have is due to anxiety lest the men of the world may misunderstand the matter, and that thereby a blow may be given to the future development of submarines. While going through gasoline submarine exercise, we submerged too far, and when we attempted to shut the sluice-valve, the chain in the meantime gave way. Then we tried to close the sluice-valve, by hand, but it was too late, the rear part being full of water, and the boat sank at an angle of about twenty-five degrees.

The switchboard being under water, the electric lights gave out. Offensive gas developed and respiration became difficult. The above has been written under the light of the conning-tower when it was 11.45 o'clock. We are now soaked by the water that has made its way in. Our clothes are very wet and we feel cold. I have always expected death whenever I left my home, and therefore my will is already in the drawer at Karasaki. I beg, respectfully, to say to his Majesty that I respectfully request that none of the families left by my subordinates shall suffer. The only matter I am anxious about now is this. Atmospheric pressure is increasing, and I feel as if my tympanum were breaking. At 12.30 o'clock respiration is extraordinarily difficult. I am breathing gasoline. I am intoxicated with gasoline. It is 12.40 o'clock.

Could there be a more touching record of the way in which a brave man met death?

More interest in submarine warfare than ever before was aroused in this country when the German war submarine U-53 unexpectedly made its appearance in the harbour of Newport, R. I., during the afternoon of October 7, 1916. About three hours afterwards, without having taken on any supplies, and after explaining her presence by the desire of delivering a letter addressed to Count von Bernstorff, then German Ambassador at Washington, the U-53 left as suddenly and mysteriously as she had appeared.

This was the first appearance of a foreign war submarine in an American port. It was claimed that the U-53 had made the trip from Wilhelmshaven in seventeen days. She was 213 feet long, equipped with two guns, four torpedo tubes, and an exceptionally strong wireless outfit. Besides her commander, Captain Rose, she was manned by three officers and thirty-three men.

Early the next morning, October 8, it became evident what had brought the U-53 to this side of the Atlantic. At the break of day, she made her re-appearance southeast of Nantucket. The American steamer Kansan of the American Hawaiian Company bound from New York by way of Boston to Genoa was stopped by her, but, after proving her nationality and neutral ownership was allowed to proceed. Five other steamships, three of them British, one Dutch, and one Norwegian were less fortunate. The British freighter Strathend, of 4321 tons was the first victim. Her crew were taken aboard the Nantucket shoals light-ship. Two other British freighters, West Point and Stephano, followed in short order to the bottom of the ocean. The crews of both were saved by United States torpedo boat destroyers who had come from Newport as soon as news of the U-53's activities had been received there. This was also the case with the crews of the Dutch Bloomersdijk and the Norwegian tanker, Christian Knudsen.

Not often in recent years has there been put on American naval officers quite so disagreeable a restraint as duty enforced upon the commanders of the destroyers who watched the destruction of these friendly ships, almost within our own territorial waters, by an arrogant foreigner who gave himself no concern over the rescue of the crews of the sunken ships but seemed to think that the function of the American men of war. It was no secret at the time that sentiment in the Navy was strongly pro-Ally. Probably had it been wholly neutral the mind of any commander would have revolted at this spectacle of wanton destruction of property and callous indifference to human life. It is quite probable that had this event occurred before the invention of wireless telegraphy had robbed the navy commander at sea of all initiative, there might have happened off Nantucket something analogous to the famous action of Commodore Tatnall when with the cry, "Blood is thicker than water" he took a part of his crew to the aid of British vessels sorely pressed by the fire of certain Chinese forts on the Yellow River. As it was it is an open secret that one commander appealed by wireless to Washington for authority to intervene. He did not get it of course. No possible construction of international law could give us rights beyond the three-mile limit. He had at least however the satisfaction when the German commander asked him to move his ship to a point at which it would not interfere with the submarine's fire upon one of the doomed vessels, of telling him to move his own ship and accompanying the suggestion with certain phrases of elaboration thoroughly American.

The rapid development of submarine warfare naturally made it necessary to find ways and means to combat this new weapon of naval warfare. Much difficulty was experienced, especially in the beginning, because there were no precedents and because for a considerable period everything that was tried had necessarily to be of an experimental nature.

To protect harbours and bays was found comparatively easy. Nets were spread across their entrances. They were made of strong wire cables and to judge from the total absence of submarines within the harbours thus guarded they proved a successful deterrent. In most cases they were supported by extensive minefields. The danger of these to submarines, however, is rather a matter of doubt, for submarines can dive successfully under them and by careful navigating escape unharmed.

The general idea of fighting submarines with nets was also adopted for areas of open water which were suspected of being infested with submarines. Recently, serious doubts have been raised concerning the future usefulness of nets. Reports have been published that German submarines have been fitted up with a wire and cable cutting appliance which would make it possible for them to break through nets at will, supposing, of course, that they had been caught by the nets in such a way that no vital parts of the underwater craft had been seriously damaged. A sketch of this wire cutting device was made by the captain of a merchantman, who, while in a small boat after his ship had been torpedoed, had come close enough to the attacking submarine to make the necessary observations. The sketch showed an arrangement consisting of a number of strands of heavy steel hawsers which were stretched from bow to stern, passing through the conning tower and to which were attached a series of heavy circular knives a foot in diameter and placed about a yard apart. Even as early as January, 1915, Mr. Simon Lake, the famous American submarine engineer and inventor, published an article in the Scientific American in which he dwelt at length on means by which a submarine could escape mines and nets. One of the illustrations, accompanying this article, showed a device enabling submarines travelling on the bottom of the sea to lift a net with a pair of projecting arms and thus pass unharmed under it.